"Use a Butterfly?" Child said.

"No. Mark V."

"Fast or slow?"

"Fast, "Coen said "Where do you hit?"

"At home. I hate the clubs."

Blue Eyes, Jerome Charyn, 1973

There is only one sport I ever excelled at. When I played it, it had the lowly name of ping-pong. Bats where called racquets and they came in two types, sandpaper or a thin rubber surface on both sides. By the time I was really good at table tennis, my bat was a Butterfly with a thick layer of spin-inducing foam, I had to worry about making ends meet. I abandoned the sport. But I have kept hidden in my small repertoire of talents a mean slam that I can pick up with the ball barely over the table and direct it to the opposite side of wherever my opponent might be standing.

I learned to play at St Ed’s in the late 50s and most of my bag of tricks came courtesy of a Hungarian classmate, Istvan Rozanich, whom I always managed to defeat. He would lose his cool. Pin-pong is all about not losing your cool. I would precipitate the situation by taunting him, "ro-sunof-a-beech."

In 1966 on board an Argentine merchant marine Victory ship for three months I learned to play the sport at a table that pitched during equatorial storms. It put the finishing touch on my slam and improved my dancing. Dancing can be helpful in playing the game.

Perhaps my affinity to the game lured me into reading the Issac novels of Newyorican author Jerome Charyn, above. Who but Charyn (a table tennis shark) would ever write a novel, Blue Eyes, about a NY plainclothes cop, Coen, with beautiful blue eyes and a mean chop with his Mark V bat? Who else but Charyn would have his tragic protagonist gunned down while playing the game in a ping-pong club of ill repute?

All the Chinaman got from Coen was grief. “Draw on me Polish. Show me who you are. You have a trigger. Just move your right hand.” Coen held on to the Mark V. He smiled into the Chinaman’s face. Measuring Coen’s smile, the Chinaman understood that there would be no satisfactions for him this far uptown, and he gripped the Police Special with both hands, conceived a target in his head a good three feet around Coen, and fired into the target. The bat jumped over the Chinaman’s ears. Coen felt a crunch from his teeth down through his groin and into the pit of his legs. He tasted blood behind his nose. His shoes were in his face. He couldn’t determine how he had gotten from the table to the wall. He was thirsty now. He remembered a peach he had bought during maneuvers in Worms, a giant red peach, a “colorado” for which he paid the equivalent of fifty cents, because the fruitman swore to him in perfect English that the “colorado” had come from South America in a crib of ice. Coen scrubbed the peach in canteen water, his fingers going over the imperfections in the red and yellow fuzz. He cut into the fuzz with his pack knife, finding it incredible that a peach, whatever its nationality, should have wine-colored flesh all around the stone. He ate for half an hour, licking juice from his thumbs, prying slivers of fruit out of the stone, savoring his own sweet spit. There was blood in his ear when he tried to swallow. His eyes turned pink. His chin was dark from bubbles in his mouth. Only one of his nostrils pushed air.

Blue Eyes, Jerome Charyn, 1973

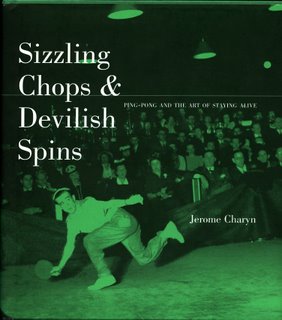

What does ping-pong mean to Jerome Charyn? In his Sizzling Chops & Devilish Spins – Ping-Pong And The Art Of Staying Alive (2001) he writes:

“Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp drizzly November in my soul,” writes Melville in Moby Dick, “I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can.” But I’m not a sailor and I can’t even swim. When I feel my own damp November, I grab my sports bag and rush to the Bastille, where my ping-pong club is located, on a little side street. I represent the subway workers of Paris and their gathering of clubs, Union Sportive du Metro. I play in a little league, against aggressive youngsters who have a serve that’s so wicked, I can barely see the ball. But it doesn’t matter. My own special racquet is like a samurai’s blade, masked with soft rubber pimples that’s called a picot. I can neutralize some of the youngsters, who can’t seem to solve the riddle of my bat. Others tear right through the soft rubber mask. But it’s a curious sport, were graybeards like myself can compete against the young killer sharks and sometimes win. I live for the sound of the ball, the pock my racquet makes while I bend my skinny knees. The fierce concentration pulls me into the fabric of a whirlwind. I dance. I dream.

In the day that I spent with Jerome Charyn in New York some years ago I learned from him that New Yorkers aren't, but Newyoricans are. He taught me to pour a bit of decent balsamic vinegar on a bowl of blackberries and vanilla ice cream. I found out that he liked to put Roumanians (his spelling) into his novels because he had once lived in a building with many Roumanians. But I was never able to rustle up enough nerve to challenge him to a game of ping-pong. Had I, I would probably not be alive to write this.

more Jerome Charyn