Jan Morris (2 October 1926 – 20 November 2020) & My Sexual Confusion

Saturday, November 21, 2020

In his 1979 book Arabia, Jonathan Raban

describes how he eventually was able to, "Just be sitting at table

among mosquitoes with glasses of Stella beer..." with his fellow travel

writer of note, Jan Morris when both happened to be in Cairo. He tells

it like this:

As James Morris, she had lived in Cairo on a houseboat in the 1950s.

James Morris had been the correspondent in the Middle East for the

London Times, and before that he had worked for a news bureau.

Jan Morris, commissioned by Rolling Stone Magazine, was revisiting Cairo

for the first time since she had changed gender, and she was nervous

about what Jan might see in James's city."

Or as Morris herself told Raban, "I'm so frightened of going back to

places and finding that I liked them better as I was than I do as I am."

Like most men I have been sexually confused many times. I remember the

first time. I was around 7 years old and the day was such a shock to me

that I even remember I was in a colectivo (a Buenos Aires bus) on the

fashionable then (and now) Avenida Esmeralda. A woman got on with a

strange little person. He or she was wearing a dress but he or she had a

shaved head. Until then I thought that boys and men had short hair and

wore pants (short or long but preferably short) and girls and women wore

skirts or dresses and had long hair. I was confused. Was she a boy or

was he a girl?

My second moment of sexual confusion happened when I was around 8. It was a Buenos Aires carnaval and people dressed up and sprayed each other with pomos

which were large toothpaste type tubes made of metal and full of

perfumed water. I had gone to see a western with my grandmother on movie

theatre row on Avenida Lavalle.

We were in the subte (the Buenos Aires underground) on our way to Retiro

train station to take me home. From my vantage point I could see the

end of the other subway car and there was a woman's bare back facing me.

She had long hair but something was wrong. Her back did not look like a

woman's. What could she possibly be? I was confused.

Not long after an American girl came to my house to play and asked me,

"Do you want to see it?" I was much too naive to figure out what exactly

I was going to see. When I saw it, "it" did not resemble at all what my

precocious (so I thought) friend Mario had told me that girls had up

front. I was confused again.

In more recent times I have been repelled by the usual macho reaction to

seeing two women together. These are usually photographs of gorgeous

women with red fingernails and fantastic bodies interacting on divans.

It ocurred to me that there are better and more interesting ways of

showing these most feminine activities. A film, Bitter Moon

directed by Roman Polanski comes to mind every time I think of this. In

this film both Peter Coyote and Hugh Grant (both playing idiots) are

left in the lurch in the end by the two women of their life, Kristin

Scott Thomas and Emmanuelle Seigner. When these two abandon their men

and proceed to dance with each other I was wonderfully shocked.

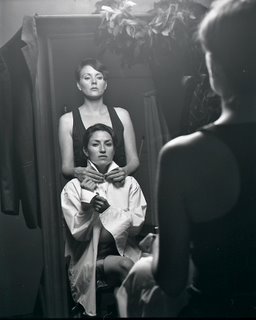

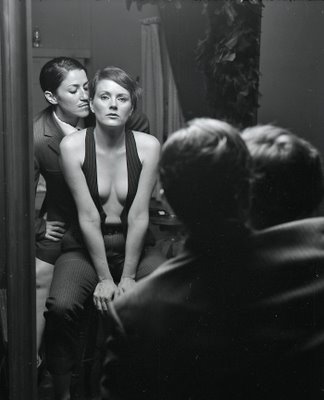

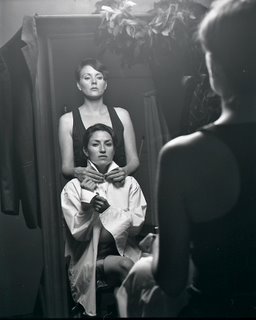

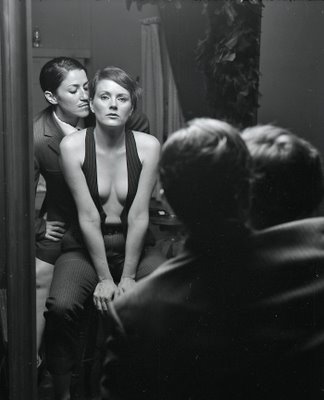

I had something of the sort in mind when I placed Ms. Hernandez and Cordelia in front of my Ikea mirror.

In one of the many books by Jan Morris that I have read I remember a

wonderful sentence that she wrote upon seeing a large portrait of

British Lord Admiral John Arbuthnot Fisher. I recall that Morris wrote

something like, " The man that I was, admired the man that is in front of

me and the woman that I am, could possibly have loved the man that he

was."

She was never confused. I am sometimes.

Ironclad Exotic

Wednesday, November 18, 2020

My Argentina has at least four definitive novels about

itself written in the 19th and 20th century (not to forget the short fiction and poems by Borges) but there is another,

actually a poem/novel written in 1872, by José

Hernández called El Gaucho Martín Fierro.

It is all about the pushing back (through war much like in the American West) by the military of the

native Argentine population as related about a man, Martín Fierro who is forcibly

conscripted. Women are rarely mentioned except in a situation where Hernández

mentions “la china del fierro”. In

Argentina a china (there were few if

any in the 19th century) is an almost derogative term for “his woman” with perhaps a darker

complexion.

For me, having been born in Buenos Aires in 1942, places

outside of my country were exotic. I thought that Americans lived in an island

called Columbia and they had broad shoulders (I had seen photographs of

American football players) wearing strange head pieces. Mexico was a place

where men slept under cactus while wearing a large hat and in Germany, grown

men wore pants.

But the most exotic was the Far East even though I knew my

mother and grandmother had been born in the Philippines. But since they were of

Spanish/Basque stock they did not look exotic.

I must have been 8 or 9 when my mother took me to lunch at

the house of her students who were part of the Chinese delegation to Argentina.

I had noticed the girls (they were all girls) before because they seemed to be

geniuses in arithmetic. Eating the strange food was my first experience with

Chinese food.

My father a journalist for the Buenos Aires Herald in 1950

moonlighted as a translator for the newly established Indian Embassy. Because

my father was a daring cook he invited his turbaned buddies from the embassy

for a home-cooked curry. That is when my street friends and I saw our first Sikhs.

To any Argentine the furthest place from our county is la Cochinchina. This was the 19th

century naming by the French of Vietnam. When we want to insult someone without

using obscene words we tell them to go “¡ vete

a la Cochinchina!” Somehow that country in Spanish sounds like an obscene

word.

So when I had my chance to photograph a lovely woman from

Vietnam, Lisa Ha, I jumped many times in glee as I would finally remove from my

20th century idea of what was exotic, now in the 21st era

of globalization, perhaps a more realistic one.

It could have ended there until a few days ago when I read

in my Sunday NY Times Book Review

Magazine about a novel by the Argentine female writer Gabriela Cabezón

Cámara (who almost won the booker prize for a translated version of her novel

in English called The Adventures of the China Iron). You would have thought

that her novel in Spanish (written from the point of view of Fierro’s girl)

would have been simply called Las

Aventuras de la China Fierro. But no! She had to use the word in English “Iron” to make it all more hilarious.

The translators are Fiona Mackintosh and Iona Macintire. I

plan to go to Buenos Aires as soon as I am able to travel so I can buy the

novel in Spanish.

Meanwhile I will take comfort with these snaps of the exotic

Lisa Ha. P.D. I was able to find Cabezón Cámara's novel in Spanish from a bookseller in Victoria, B.C. It is a lovely book with lots of fascinating info on the flaura and fauna of the Argentine Pampa. It is about the relationship between two women. One of them is a red-haired Scot. There is a chapter of lesbian shenanigans that made me blush. And to top that she states that the manly Martín Fierro may not have been so!

Donde el eco se funde con el grito

Tuesday, November 17, 2020

En marzo

del 2017 tuvímos una huésped por dos semanas en nuestra casita en el barrio

Kitsilano de Vancouver. Sandrine Cassini es una bailarina francesa que durante

unos años bailó para Ballet BC. Nos hicimos amigos y por varios años me posó.

En esta ocasión mi foto favorita resultó esta que tomé con mi Mamiya RB-67 con

película instantánea Fuji. La tomé sobre el diván psiquiátrico ubicado en nuestra

pieza con el piano. No tuve que buscar mucho para encontrar esta hermosa poesía

sobre las piernas de una mujer. Los escritores latinoamericanos para mí escriben

con más sensualidad que sus colegas de otros idiomas. El caso del uruguayo

Mario Benedetti es un caso en particular.

Piernas

Las

piernas de la amada son fraternas

Cuando

se abren buscando el infinito

Y apelan

al futuro como un rito

Que las

hace más dulces y más tiernas.

Pero

también las piernas son cavernas

Donde el

eco se funde con el grito

Y

cumplen con el viejo requisito

De buscar

el amparo de otras piernas.

Si se

separan como bienvenida, las piernas de la amada, hacen historia

Mantienen

sus ofrendas y en seguida enlazan algún cuerpo en su memoria

Cuando

trazan los signos de la vida

Las

piernas de la amada son la gloria

Mario

Benedetti

A 1928 Kotex Ad - Edward Steichen & the Grumman F6F Hellcat

Monday, November 16, 2020

Many of the 20th century photographers I have admired since

I became interested in photography around 1958 have been photographers who were

not one-trick-ponies. They were versatile. One of the most versatile was Edward

Steichen.

Edward Jean

Steichen (March 27, 1879 – March 25, 1973) was a Luxembourg/American

photographer, painter, and curator, who is widely renowned as one of the most

prolific and influential figures in the history of photography.

Credited with

transforming photography into an art form, Steichen's photographs were the

photographs that most frequently appeared in Alfred Stieglitz's groundbreaking

magazine Camera Work during its publication from 1903 to 1917, with Stieglitz

hailing him as "the greatest photographer".

A pioneer of

fashion photography, Steichen laid claim to his photos of gowns for the

magazine Art et Décoration in 1911, being the first modern fashion photographs

ever published. From 1923 to 1938, Steichen served as chief photographer for

the Condé Nast magazines Vogue and Vanity Fair, while also working for many

advertising agencies, including J. Walter Thompson. During these years,

Steichen was regarded as the best known and highest paid photographer in the

world.]

After the United

States' entry into World War II, Steichen was invited by the United States Navy

to serve as Director of the Naval Aviation Photographic Unit. In 1944, he

directed the war documentary The Fighting Lady, which won the 1945 Academy Award

for Best Documentary.

From 1947 to 1961,

Steichen served as Director of the Department of Photography at New York's

Museum of Modern Art. While there, he curated and assembled exhibits including

The Family of Man, which was seen by nine million people. In 2003, the Family

of Man photographic collection was added to UNESCO's Memory of the World

Register in recognition of its historical value.

In February 2006, a

print of Steichen's early pictorialist photograph, The Pond—Moonlight (1904),

sold for US$2.9 million—at the time, the highest price ever paid for a

photograph at auction.

Wikipedia

Not mentioned in the above Wikipedia citation is the fact that in July 1928 he took the

first ever Kotex ad with a woman in it. Also almost unknown is the fact that

his model was Lee Miller who was a muse, assistant and a photographer for Man Ray. She

then became a photojournalist in WWII (with that other potographer of note Margaret Bourke-White) and when Miller arrived in Munich in 1945 she insisted she be photographed in Hitler's tub

At Macleod Books ( not only a Vancouver treasure but a

Canadian treasure) I found Edward Steichen’s beautifully written and

illustrated The Blue Ghost (the Japanese Navy nickname for the US carrier Lexington) which catalogues his stint on the Lexington

from 9 November 1943 to 23 December 1923. In this book are his photographs and

his staff of the torpedoing of the Lexington.

This book amply shows that good photographs and good

writing go hand in hand and jointly are better that one or the other.

The photograph of the cover of The Blue Ghost, a Grumman

F6F Hellcat is justly famous because of its blur that demonstrates the speed of

the plane taking off. Steichen explains how he shot it in the book. Read below.

My Steichen Blogs One Two Three

Memory and Hospitals

Sunday, November 15, 2020

Every time I drive on 12th Avenue past the Vancouver General

Hospital I notice that their smokestack has been demolished. What is left of it

is wrapped in what looks like surgically

clean plastic.

I remember

another time when for an article on VGH cuts for the Georgia Straight I must have convinced some nurse

to pose for me and represent the despair of the effects of financial cuts to

our hospital system.

For me

hospitals began as a mysterious wonder. In our home in Buenos Aires in the

early 50 on Melián Street empty but beautiful funeral carriages (with beveled windows)

would trot (the horses had black plumes on their head) in the direction of the

Pirovano Hospital on Monroe and Melián about five blocks away. They would

return and I would be able to see the coffin inside.

The

hospital to me was painted a menacingly dark green and I never did enter it.

My

perception of that hospital changed when in 1966 at my desk as a conscript of

the the Argentine Navy who translated documents for a US Naval Advisor I received

a phone call from my almost-uncle Leo Mahdjubian. In his British English (even

though an Armenian he had worn a kilt in the Black Watch in WWI) said, “Your

father kicked the bucket yesterday in front of the Pirovano. A police sergeant took

him in but he was pronounced dead. Because of the intervention of the policeman

you must report to the police station to sign some documents.

At the

police station the policeman at the desk told me that I could not possibly be

the dead man’s son as the son had been there a few hours before to sign. That

is how I soon got to meet my half brother.

The Sergeant

who took my father to the Pirovano called me to tell me he had taken the

liberty of emptying my father’s pockets as they would have disappeared in the

hospital. He told me that there was a large sum of money in his pocket that my

father was saving to bribe a General and get me out of my conscription.

At my age

of 78 I wonder if my last days will be spent in a hospital or if I will directly

go where even kings go alone.

|