Kiki de Montparnasse

Saturday, November 07, 2009

A couple of months ago I received a call from Patrick Blaeser who is the Program Coordinator: Certificate & Part Time Programs at Focal Point. “Alex, I have an idea of a course that you might like to teach. It would be called portraiture through the ages.” I thought about it and told him I would get back to him.

In the last few years I have been thinking a lot on how photography has progressed since Niépce took that first picture from his kitchen window in 1824. Because I was raised with books (I am a pre-internet baby!) I have many photography books in my library. I have amassed a considerable collection. My memory is still good. I remember most of the photographs of all of those books.

Without really knowing it, when I take a photograph, there is always an element of that photograph memory of the past. In some way every snap of my shutter is inspired by those photographs. But they are not only photographs of the past they can also be inspired by a painting or a sculpture. These works can be by artists who may be contemporaries to photography but many also preceded the age of photography.

As an example when I teach nude photography and we have a male model, sooner or later we explore Rodin’s The Thinker or Michelangelo’s David. Just about every time I bring in a mirror into a studio I recall Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas.

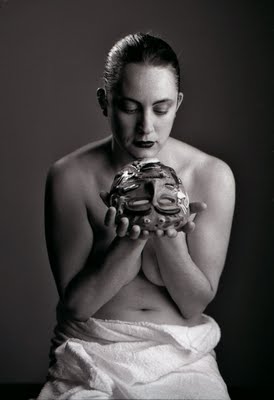

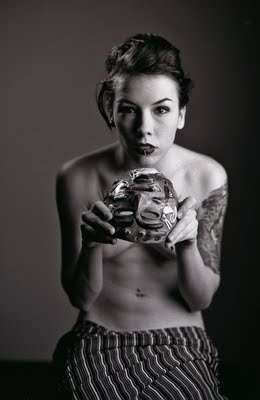

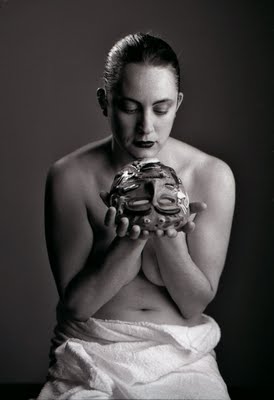

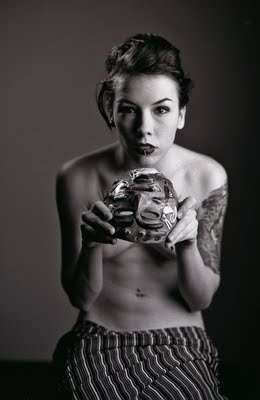

I didn’t linger much before I called back Patrick to tell him I was very excited. The class began six Wednesdays ago. It is a three hour class held every Wednesday for ten weeks. This last Wednesday we brought back two of our favourite models, Shannon and Jerry. Shannon is voluptuous and Jerry is slim but curvaceous, nonetheless. Jerry admires Bettie Page. Jerry’s skin is white and she sports several tattoos and body piercings in strategic areas.

In this sixth class we worked with the inspiration of some of the photographs that Man Ray took of his model Kiki in the 20s. The more famous one is called Kiki, Ingres’s Violin. The joke of the name is that in French that name also is about obsession. Perhaps, as some say, Man Ray was not particularly inspired by the nudes of Ingres as much as using him as the excuse to get Kiki to take her clothes off.

The second picture is called Noire et blanche. In the 1920s African masks were all the rage. Even Picasso was part of that primitive movement. Since I did not have an African mask at home I brought a Mexican one made of clay.

For the f-holes we used dry erase writing board markers. One of my students, Nicky was a skillful wrapper of turbans. She also drew the f-holes and insisted in making stencils out of paper. In the first picture you can see her silhouette as she takes her picture of Shannon.

The second artist we worked on was El Greco. For this we took advantage of Jerry’s slimness. Alas I was too busy making sure everybody was doing what they were supposed to be doing so I was not able to snap any of the El Grecos. For the pictures you see here I used a Nikon FM-2 with a 50mm F-1.4 lens. Shannon could afford to rest for this as she had been very good in a previous class as John Singer Sargent's Madame X.

I worked with Kodak Tri-X and my exposures were 1/60 at f-2. I used the modeling lights of the flash units as I did not want to take shooting time from my students.

It has been a while since I have felt so excited about a class I teach. Thank you Patrick.

Addendum: Unlike our efforts where we drew the f-holes on the back of the models Man Ray drew them on his prints. It would be interesting how many of these he drew and if all those originals of his are really reproduction copies of the few he actually drew.

more Kiki via Peggy

Revealing The Serendipity Of Failure

Friday, November 06, 2009

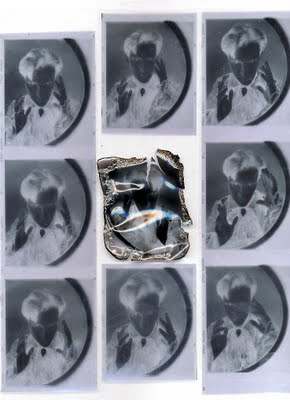

I like to think of the serendipity of failure as one of the most welcome methods of achieving new results with the photographic process. Sometimes that failure is suppressed for years (in this case it was a period of 24 between the taking, 1985 and its revealing.) It is interesting for me to point out that to develop a negative or print in Spanish we use the verb revelar which also means to reveal as well as to make visible that which is hidden.

I find the word magical as it stresses less the mechanical process and more on what the image itself will show of itself, its maker and his subjects.

The failure here involved opening the film back to light after the exposure of the pictures. The event was at the Sub Ballroom at UBC. It was a concert with The Cramps and two local bands of note, the Modernettes and Slow. I don’t think that any of the pictures (there are 7 exposures in my files) were ever used. There may have been more but the sudden opening of the back would have ruined at least half of them. At the time I was using 220 film which meant I had the possibility of exposing 20 frames.

With the advent of good scanners I am able to “restore” these pictures to some degree of contrast and sharpness while retaining some of the intangible charm of the inadvertent gross overexposure.

More Failure.

zemblanity.

The Cramps.

Bishop's Castle, Capablanca, Capdevila & Chess

Thursday, November 05, 2009

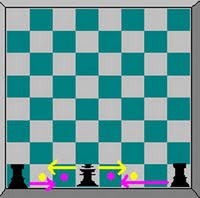

Arturo Capdevila El tablero de ajedrez (fragmento) " Como en la vida, todo es problema en el ajedrez, desde la apertura hasta el mate. Pero todo es equidad y todo es ley. Tengo aquí peones, Caballos, Alfiles: están medidas mis potencias. Puedo adquirir, sin embargo, nuevas fuerzas por la combinación acertada de las que me han sido consentidas. Y, a la inversa, puedo disminuirlas o perderlas. Nadie sino yo tendrá la culpa de esto. Una combinación errónea me traerá siempre a menos, bajo el jaque del rival. De donde se infiere, provechosamente, que la violenta ambición es perversa consejera, y que tan sólo se ha de tomar en cuenta el interés de la armoniosa verdad. La multiplicidad de peligros de que vivimos rodeados se evidencia en el tablero. Hemos jugado por fin. ¿Qué hará el adversario?... Es el dueño de innumerables posibilidades; el mero paso de su peón, con ser nada más que un peón, puede comprometer todo mi plan y ocasionar mi ruina. Lección incomparable, que nos instruye en la suprema ley de la relatividad. ¿Y lo que se pierde, se pierde para siempre? El ajedrez nos da un consuelo. Si cuidamos la marcha de los ínfimos peones, tan pequeñitos como son, apoyando su avance con bien distribuidas fuerzas, alguno de ellos entrará a los últimos cuarteles del adversario y será nuestro precio de recate por la pieza grande que entregamos en temerario arranque al lazo del enemigo. Así, del propio error viene a servirse el ajedrizta paciente para la ulterior victoria. Parece que por tales caminos se nos aleccionará de que no hay modesta intención ni altruista constancia que al cabo no fructifique. Porque todo este juego se funda en el ejercicio altruista de los poderes, como se ve de inmediato cuando se considera que siendo el Rey la pieza menos útil, por él pelean las demás, denodadas y terribles. También se advierte que la pieza jaqueada no atiende nunca a su particular salvación sino a la del conjunto que se le sobrepone. "Arturo Capdevila (1889, Córdoba, 1967 Buenos Aires) Yesterday I toured our garden and saw one of my roses, uncharacteristically in bloom this late in the season. It is an English Rose called ‘Bishop’s Castle’ Two years ago when I first purchased it, the bush was glorious with multi canes and blooms. But it has ultimately been a poor grower. Now it is a sorry spindly thing. I am not all that sure it will come back for next spring. The very thin cane was bent over and one of the blooms was dragging on the ground. But one of he others was in all of its glory and in spite of the cold weather I could smell its exquisite scent. It is a scent that will remain in my memory, as the days become wetter, colder and bleaker, until spring. I wondered why the rose had the name. The first thought in my mind was that it could have something to do with chess. I quickly shifted my thoughts to other possibilities as the only chess connection would have to do with moving both the bishop and the knight out of the way and or the queen if one were to castle (the only move in chess where two chess pieces, the king and the rook, are moved simultaneously).  But while I finally found out that the name has to do with a small market town in Shropshire (close to where David Austin hybridizes his roses) by the same name, chess lingered in my mind. I began to play chess when I was 8 but I abandoned it when I was 20. I realized I could never be anything but a competent player. In losing in chess one quickly learns to eliminate all excuses, and what is left, is surely a lack of intellectual activity and a torpid movement of electrical impulses in one’s neurons. Simply put, I was too stupid to be a good chess player.  Until it finally sank in, I read books on chess and my hero was the Cuban chess master with the beautiful name, José Raúl Capablanca. I had a two-month chess rennaissance in 1966 when I was on board a slow Argentine ELMA (the Argentine merchant marine) Victory ship, the Rio Aguapey en route from Buenos Aires to Veracruz. As soon as the captain Guillermo Magliorini found out I played he summoned me every night to his quarters for a match. I think that we were pretty even so when I disembarked my pride was almost intact. In the late 50s I would take the bus to downtown Mexico City to Calle Palma. Calle Palma had blocks and blocks of chess stores where I would stare at chess sets I could never afford to buy. Most of us, in those days would buy the cheap and hollow plastic pieces. We would fill them with sand to make them heavy and then we would glue on the bottoms the finest green felt we could find. The chess board was another problem. For years I had a foldable cardboard one but I finally was able to save enough to get a wooden one. I often would go to Chapultepec Castle to feast my eyes on the most beautiful chess set I had ever seen. The black obsidian players were Moctezuma, Cuauhtemoc and the fierce Aztec warriors. The jade players were Cortez, his captains and his soldiers. The chess board consisted of inlaid squares of obsidian and jade. The set disappeared in the early 70s. In the mid 90s I returned to Mexico City and I was able to secure an interview with one of the castle’s curators. She told me that the set had never existed and that I must have been confused with some other museum. Of late I have been thinking that I should buy a chess set and teach Rebecca. I am sure that her neurons would be able to accommodate more chess activity than her grandfather’s.

Dr. Burnett's Materiality

Wednesday, November 04, 2009

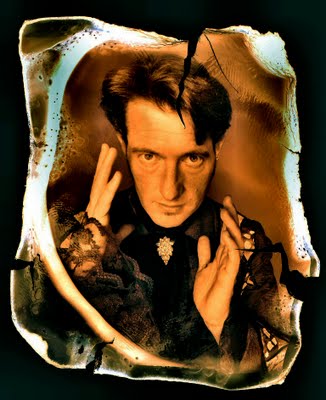

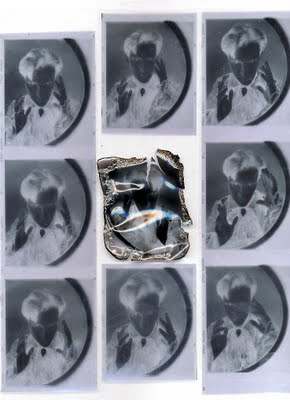

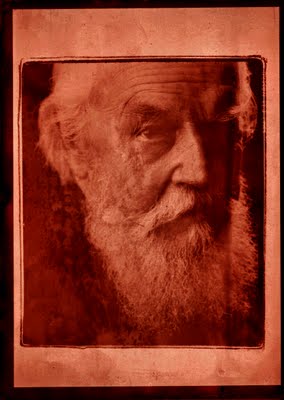

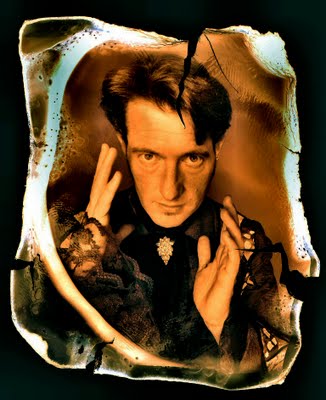

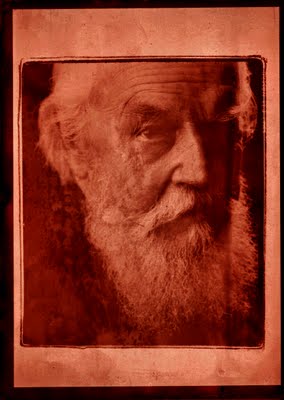

There is a story I read long ago about American photographer Edward Steichen. It seems he was near death. His housekeeper was watching him (broom in hand) and thinking that she should ask Steichen for some advice before the man died. “Mr. Steichen, my son wants to be a photographer. Would you have any pointers for him?” Visibly affected by the question, Steichen made a supreme effort to lift his head from his pillow and whispered, his voice cracking with emotion, “Don’t send him to school!” In this day and age of the takeover of amateur (citizen) journalism and amateur (citizen) photojournalism I question the relevance of journalism schools, universities and technical institutes that have journalism courses. I would think that journalism is as dead as the uniqueness of the images found in Flickr and Facebook. Everybody had a Colt Peacemaker by the time the 19th century was coming to a close. Gunfighters became an endangered species and disappeared. Footage of Iranian demonstrations comes via cell phones on the BBC TV news channel. With the death of Avedon, Newton and Penn I can no longer discern individual photographic style. The new style of our 21st century modernity seems to be uniformity. I teach photography at a couple of schools. I agonize as to my relevance as a teacher. I feel that unless I declare Time-like that Photography Is Dead I am fooling my students into a false promise of money and success in a field where the mantra is “free is the best price”. I find comfort in the idea that school sometimes has its advantage. Around 1976 I was struggling to teach myself how to print colour negatives and slides in my darkroom. I postponed and postponed. One day my Rosemary said, “You are starting a course on colour printing at Ampro Photo Workshops on Monday.” I was paying to learn. I did my homework out of guilt. I learned how to print. School had provided me with a structure. Most of my students can run circles around me with their knowledge of the inner workings of their DSLRs. They know all about white balance and the intelligent ordering and fixing up of their images with photo programs like Lightroom and Photoshop. I attempt to teach them lighting. This is something I am sure I know something about. But when you extend a class to several weeks what else can I possibly bring into the learning crucible? I try to explain to my students how knowledge of photographers and artists of the past can inspire us to imitate, vary, improve, modify and better still they inspire us to inspire us. I tell them about photographer Bert Stern who pioneered the use of the white background and the concept that photographically, less is indeed more. I tell them that he “invented” cleavage lighting for Cosmopolitan. In the end I am stuck with the frustration of trying to teach them in a ten class course the idea of conceptualizing a photograph. I borrowed a bit from photographer Minor White who wrote about the idea of pre-visualization. This involved looking at a scene, imagining it in one’s head and then taking a picture that expressed that image in the mind with some sort of near perfection in reality. Every time I take a picture it is almost as if every photographer (and artist, painter and sculptor) is put into a blender. I mix it all up and pour out my modification of all their ideas. I know I can teach the lighting and some of the mechanics of picture taking. But how can you teach students the thought process? For all my years as a photographer I had what I perceive as an advantage. This is that I think in three dimensions. All the photos on this blog involve the idea of objects that occupy space. They cast shadows, they weigh, they smell, they change with time. In a short but pleasant chat with Emily Carr University of Art + Design, Dr. Ron Burnett yesterday he mentioned a word, perhaps a word of his invention which finally explains for me the concept that I am trying to grasp. This concept is the very one I want to transfer to my students. Dr Burnett improves upon the idea of three-dimensionality and its importance in conceptualizing images, with the word materiality. It is the materiality of things that a photographer manipulating images with Photoshop somehow misses. This process of beginning with objects and transferring them to the latent image of actual film is being lost as photographers manipulate penguins into being on the sands of the Sahara Desert.  Dr. Burnett hints that painting and photography can only survive if both survive. My granddaughter Rebecca kept asking me if the paintings on the wall (at the recent Vancouver Art Gallery exhibition of Dutch painting) were indeed originals. As Dr. Burnett sees it she was asking me about their perceived reality. Were they indeed occupying space because they were three-dimensional? They had materiality. They were not photons on a computer monitor. As an example I was assigned some years ago to photograph baritone Brett Polegato for a Vancouver Opera production of Mozart’s Don Giovanni. Those familiar with the opera know that this inveterate womanizer gets his deserved due and burns in hell in the end. I wanted to convey this idea of burning in hell. I was not given access to props, wigs or anything. I had Polegato in my studio wearing his street clothes. So I came up with the concept and took 9 pictures (I did not need more) that were relatively tight portraits. I picked the best negative and lit it with a match. It burned beautifully and the cellouloid even cracked at the right place. The film had warped in the heat. I then scanned the result. While a digital photographer might imitate my concept with Photoshop, it is the concept itself that (in my opinion) probably seems unlikely to be conceived by the photographer. You have to think in the materiality of things. The Other Side of Two DimensionsDr. Ron Burnett's Blog

The Film Samuel Z. Arkoff Never Made

Tuesday, November 03, 2009

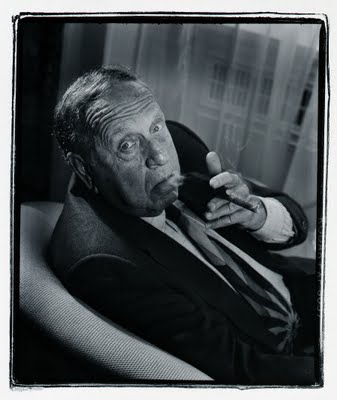

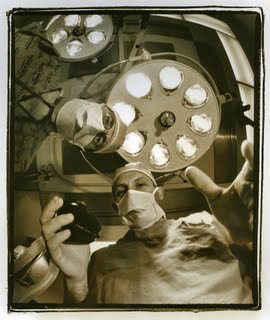

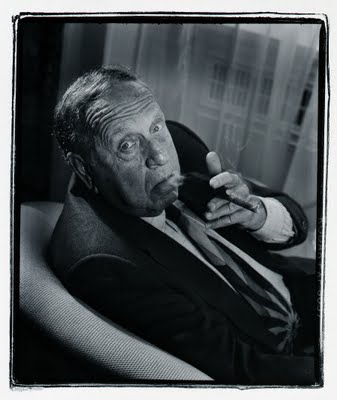

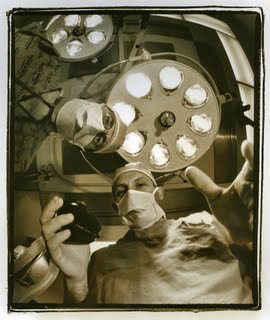

In his 1992 autobiography Flying Through the Seat of My Pants low-budget movie mogul Samuel Z. Arkoff wrote, “Thou shall not put too much money into any one picture. And with the money you do spend, put it on the screen; don’t waste it on the egos of actors or on nonsense that might appeal to some highbrow critics.” Of my session with Mr. Arkoff at the Hotel Vancouver in May of 1991 I remember next to nothing except that he knew how to pose and I was not bothered by his cigar. At the time I smoked them. Arkoff and I compared notes on the differences between Montecristos and H Upmanns. I favoured the former and he was smoking the latter. Of the 463 films he made I only saw one, Machine Gun Kelly with Charles Bronson. The reason for this apparent anomaly is that I had inherited from my mother a taste for films with good (and expensive!) actors. Joseph Cotten and Samuel Arkoff probably never met or worked in the same circles.  I was never a lover of B-movies unless they were Westerns ( Colt .45 with Randolph Scott) or science fiction ( This Island Earth). The first "horror" film I ever saw and one of my last, I saw with my father around 1951. It was Abbot and Costello Meet Frankestein. I was scared to death by the sudden appearance of Bela Lugosi's Dracula. This South American who until now has never been able to stand Hollywood musicals (How can it be that perfectly sane actors suddenly begin to sing to each other? ) is suddenly enjoying a few. And most recently I went to listen to Stephen Sondheim talk about his plays were actors do just that, sing and talk. Perhaps Mr. Arkoff and I have some catching up. There are those 462 films I have not seen. There is one that I will never see that Mr. Arkoff never made. The film that was never made would have featured two naturals, two anesthetists, Tony and Igor. Arkoff’s film would have been called Going Under.

John Armstrong - Rebel Kind

Monday, November 02, 2009

I first met John Armstrong (aka Buck Cherry) around 1979. I was one of the judges for a battle of the bands type contest at Gary Taylor’s Rock Room on Howe Street. I was no expert in rock like my In One Ear associate from Vancouver Magazine. Gary Taylor liked me because I was cheap. He could buy me for the night with Perrier while some of the other judges were paid in expensive booze and white powder.

I was not prepared for a band like the Modernettes. They featured a roly-poly young man with a sneer and an American Civil War kepi (the rebel kind), a tall blonde with legs from here to Dunsmuir called Mary Jo Kopechne (she liked to explain that both she and her namesake could not swim) and a non-stopping drummer called Jughead. This trio, plaid very loud and very off-key. I hated them. I never voted for them.

But they did grow on me and learned to appreciate their fast, furious and short tunes. They did for my ears what Colman’s did for my sinuses.

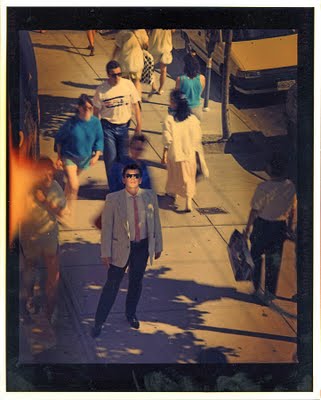

The first picture you see here I have a vague idea that it might have been around 1982 and that I took it at UBC. The Modernettes and Slow (that’s Anselmi the lead singer of Slow on the far left, then John followed by Mary Jo whose hair covers part of her face). These two bands were warm-up acts for the Cramps.

Sometime at the end of the 80s I suggested to John (he had wit and lots of knowledge gained from watching TV until all hours of the night after concerts and or reading lots of novels) that he purchase a Harris Tweed jacket, a shirt and tie and go to Charles Campbell (then editor of the Straight) and ask for a free-lance writing job. This paid off, and in short order John and I were off to interview and photograph Vincent Price and Dennis Hopper.

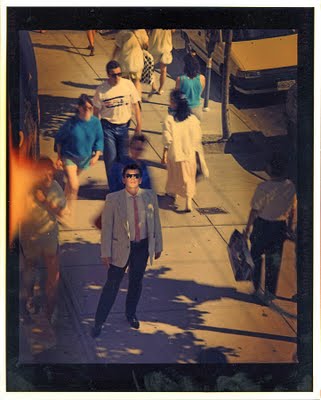

In the early 90s writer and friend John Lekich wrote an article about alternative medical practices. I was asked by art director Chris Dahl to not only take the pictures with colour negative but he expressly demanded I print them. If that was not enough he suggested (strongly) I only use mirrors for lighting. This particular shot of Armstrong I took on Robson. It had something to do with some sort of weird self-help. Writer Lekich was next to me on the top floor of a restaurant aiming the mirror. I had asked some friends to walk around Armstrong quickly.

It was all a pain in the neck. I hated printing the pictures. I wanted to punch the art director in the nose. Looking back at those days I now know it was all good fun. Fun has now been diluted to nothing and if I ran into Dahl on the street I would hug him.

Rebel Kind.

Saved By Ibsen

Sunday, November 01, 2009

I hate Halloween. I wrote those very same words in Halloween 2007. Both Halloweens, that one in 2007 and last night's, had a happy ending. The first one was courtesy of Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie and last night it was a production of Henrik Ibsen’s The Master Builder at the Telus Studio Theatre performed by my friend actor/writer C.C. (Chris) Humphreys. In both occasions we did not have to stay at home and hand out candies and listen to doorbells, loud knocks and the incessant shouting, “Happy Halloween.” If I could I would be another Grinch. And just like in that other Halloween, Rosemary and I stopped at the granddaughters’ to take their snaps before they went out trick or treating. I make my formal request now, "Chris, plan some Richard Brinsley Sheridan for next Halloween. I don't want to stay home."

Halloween & Robertson Davies

October 31, 1990

Haunted by Halloween

By ROBERTSON DAVIES

TORONTO -- Halloween deserves a house cleaning. Our strongly superstitious age needs Halloween, but cannot do anything with it in its present degenerate form.

Halloween has been thrust too much into the hands of children. Dressing children as ghosts and witches, and sending them out on the night of Oct. 31 to demand tribute from the neighbors, or perhaps to proffer collection boxes for a variety of more or less worthy charities, is contrary to the deeper meaning of Halloween. The old festival is not childish, nor associated with good works and community spirit.

The deeper meaning? What lingers today is a foggy recollection of the great Celtic festival of the Death of the Year. The Celts divided their year into the growing months and the resting months. The former began on the first of May with the Feast of Beltane, where the returning sun was welcomed by huge bonfires on the hills. The latter started after the harvest had been gathered. The waning of the sun was marked by the Feast of Samhain, a two-day affair, celebrated after sundown on Halloween and on All Saints' Day, Nov. 1.

It was the Christian Church, of course, that instituted the feast of All Saints. The church was crafty about adapting pagan celebrations to its own purposes, and when it set about its methodical substitution of Christianity for the old Celtic religion, it carefully noted that at Samhain the Celts remembered their ancestors and their heroes, and did them honor in a number of ceremonies, including, so the missionaries said (but the evidence of missionaries must always be carefully weighed), human sacrifice. How logical, then, that the old feast should serve the new faith and be-come a time when the saints were recalled on Nov. 1 and all the other faithful dead on the day that followed, called All Souls'?

If we were to take a new look at Halloween, what might we do? Surely revive the custom of giving some respectful heed to our forbears.

We of North America are not so likely to do this as are the peoples of the rest of the globe. Is it because of our driving ambition to do better than our parents? Like it or not, to reach middle age with less money or less prestige than our father had is somewhat to lose face. Stupid of course, when put like that, but who is prepared to argue that we are not stupid in several important ways?

Nevertheless, our forbears are deserving of tribute for one indisputable reason, if for no other: without them we should not be here. Let us recognize that we are not the ultimate triumph but rather we are beads on a string. Let us behave with decency to the beads that were strung before us, and hope modestly that the beads that come after us will not hold us of no account merely because we are dead.

Today and tomorrow are the proper days for such reflection. It need not detain us for more than a few minutes, but it should be sincere. A few gentle thoughts or even -- I hardly know how to put it without moving you to indignation or laughter -- a brief prayer would not come amiss, and might turn your thoughts in a fruitful direction.

There have always been people who give no regard to their forbears, and it was they who were thought in the days of the old Celtic religion to suffer on Halloween. That was the night when the spirits of the neglected or affronted dead took vengeance on their unworthy descendants. They were on the rampage as bats and owls, ghosts and bogles, and they were not always careful where their vengeance fell. To be out on Halloween was to run great risk of physical or psychological harm, for it was then that the underworld of chaos and death settled old scores.

Wise folk, long after Christianity ousted the Old Religion, kept indoors on the night of Samhain and followed tradition by trying to foresee the future. There are still people who remember bobbing for apples at Halloween parties. It is a method of divination now turned into a game. My father recalled that when he was a boy in rural Wales, girls used to drop molten lead into cold water on Halloween because the lead would surely take the form of the first letter of their true love's name and if it did so he would marry them.

Fortunes were told by "scrying," which was to see images in a basin of water (later a crystal). Soul cakes -- rather than shortbread -- were baked and given to the children who went "souling" from door to door -- the beginning of the modern trick-or-treat. By the 19th century, we can presume, it was safe to go outdoors.

Did I not speak earlier of this as a strongly superstitious age? Who can deny it, when fortune tellers of all sorts prosper as they have not done in 50 years, as sophisticated young business people resort to them, within a few yards of the great Market of Phantoms, Wall Street itself? Has there ever been such a brisk trade in crystals and tarot cards? Have wizards ever advertised so unequivocally in the very best publications?

There are laws almost everywhere against witchcraft but how often are they invoked? There are covens of liberated women who let it be known that they are witches but are anxious to have it understood that they are White Witches, who do no harm and simply get together to invoke the Great Mother, the supreme Nature Goddess, and eat a few vegetarian dishes. Their attitude shows the cast of mind that has gelded and trivialized Halloween.

The Great Mother, who is said to have anticipated the reign of the Great Father by several millennia, was, like Nature, not unremittingly benevolent. She had -- or should I say has -- an eerie, nasty side, and the rout of evil spirits on Halloween was only one of her ways of letting it be known. She had three natures -- Virgin, Consort and Hag; the Hag was rough and, in the form of children got up as witches, still makes a farcical appearance on Halloween.

What might we profitably do on Halloween? Look backward, and consider those who went before us. The road ahead is inevitably dark, but to see where we have been may offer unexpected hints about who we are, and where we should be heading. Triviality about the past leads certainly toward a trivial future.

|