That Ingenious Hidalgo - Monsignor Quixote

Monday, November 23, 2009

“Monsignor,” he said, “there is one question I have often asked myself, a question that is perhaps likely to occur more frequently to a countryman than to a city dweller.” He hesitated like a swimmer on a cold brink. “Would you consider it heretical to pray to God for the life of a horse?”

“For the terrestrial life,” the bishop answered without hesitation, “no – a prayer would be perfectly allowable. The fathers teach us that God created animals for man’s use, and a long life of service for a horse is as desirable in the eyes of God as a long life for my Mercedes, which I am afraid, looks like failing me. I must admit, however, that there is no record of miracles in the case of inanimate objects…"

“I was thinking less of the use of a horse to its master than for its happiness – and even for a good death.”

“I see no objection to praying for its happiness – it might well make it docile and of greater use to its owner – but I am not sure what you mean by a good death in the case of a horse. A good death for a man means a death in communion with God, a promise of eternity. We may pray for the terrestrial life of a horse, but not for its eternal life – that would surely be verging on heresy. It is true that there is a movement in the Church which would grant the possibility that a dog may have what one may call an embryo soul, though personally I find the idea sentimental and dangerous. We mustn’t open unnecessary doors by imprudent speculation. If a dog has a soul, why not a rhinoceros or a kangaroo?"

“Or a mosquito?”

“Exactly, I can see, father, that you are on the right side.”

“But I have never understood, monsignor, how a mosquito could have been created for man’s use. What use?”

“Surely, father, the use is obvious. A mosquito may be likened to a scourge in the hands of God, it teaches us to endure pain for love of Him. That painful buzz in the ear – perhaps it is God buzzing.”

Father Quixote had the unfortunate habit of a lonely man: he spoke his thoughts aloud. “The same use would apply to a flea." The bishop eyed him closely, but there was no sign of humor on Father Quixote’s gaze: it was obvious that he was plunged far in his own thoughts.

“These are great mysteries,” the bishop told him. “Where would our faith be if there were no mysteries?"

Monsignor Quixote, Graham Greene, 1982, Simon and Schuster, New York

Of late I have stumbled into wonderful books (and films) thanks to my new policy of relinquishing my addiction to buying books and settling into enjoying the charms of the hidden/random (via raiding the shelves without a plan) stacks of the excellent Vancouver Public Library.

It was only yesterday that I was in search of a book for my Rosemary who is struggling with an intense computer course that involves Word, Quick Books, Excel and PowerPoint. I am unable to help her as my knowledge of Word is limited to writing on my monitor and availing myself of Word’s best feature, Word Count. My friend Paul Leisz put together a PowerPoint presentation (he was in dismay when I told him I didn’t want fades, music or any kind of special effects). I use that PowerPoint presentation, over and over and all I do is replace the old pictures with new ones. That is as far as I can go with PowerPoint.

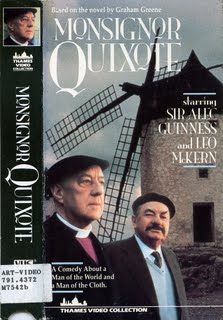

The Renfrew Branch of the library had a copy of Word 2002 for Dummies. Off I went to get it. It was there that in the stacks I randomly found a made for British TV film I had seen back in 1987. It was from the series Great Performances and directed by Rodney Bennett. It was the adaptation of Graham Greene’s slim 1982 novel Monsignor Quixote. The film (what I remembered of it with a glow in my heart) has Alec Guinness playing the stoic small-town (El Toboso on the plains of La Mancha in Spain) parish priest and Leo McKern as his friend the recently ousted (with a sort of fair election) communist mayor. Ian Richardson plays (in a short but extremely satisfying performance) an Italian monsignor (with lots of clout we find out) from an obscure local in Africa who is saved by Quixote’s vague knowledge of car engine repair. The prelate is stuck in the middle of nowhere, a parched Manchegan plain, in his Mercedes when Father Quixote drives by in his ancient Seat (a Spanish Fiat which he affectionately calls Rocinante). The Bishop of Motopo enjoys Quixote’s hospitality especially his Manchegan wine and the steak (the bishop never catches on that it is a horse meat steak). Quixote’s hospitality is rewarded by a letter from his local bishop (one with whom Quixote cannot get along) informing him that the Holy Father has promoted him to monsignor (via a recommendation from the Bishop of Motopo) and that he can now wear the purple bib and socks of that lofty ecclesiastical office.

I will not reveal anymore about this really good film that had me feeling entertained and happy but also depressed as I watched it alone last night while Rosemary struggled with the inhuman logic of Microsoft. But I must mention that the dialogue was so good that in one particular moment (see below) my head opened up to a rush of memories of my past that it reminded me of the intensity of the rains we have been getting of late. As soon as the film was over I took out my Monsignor Quixote and I was delighted that Graham Greene with the help of the credited writer Christopher Neame and the uncredited Miguel Cervantes somehow made that dialogue just about identical to the novel. Both of the passages here which I copied from the book are virtually the same to the film’s dialogue.

He [Sancho] stared gloomily into his glass of wine. “Oh, I laugh at your superstitions, father, but I shared some of them in those days [as a young student in Salamanca]. Is that why I seek your company now – to find my youth again, that youth when I half believed in your religion and everything was so complicated and contradictory – and interesting?”

Monsignor Quixote, Graham Greene, 1982, Simon and Schuster, New York.

The philosophical musings on the possible existence of a soul in a dog charmed me. But it was in the latter quote (when I heard it in the film) …everything was so complicated and contradictory – and interesting…that grabbed my attention and suddenly I could feel and miss the ghostly presence of the amputated limb that I had lost slowly, surely and inevitably all these years. It was my complicated, contradictory and interesting Catholic faith.

Thanks to my daily-mass-going grandmother and Brother Edwin Reggio, CSC, who taught me religion at St. Edward’s High School, I was able to practice in reality that tune that my father and I used to sing in bed, usually after we sang My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean, (I didn't know then that my father’s rousing singing may have been alcohol induced):

Onwards Christian Soldiers.

Onward, Christian soldiers, marching as to war,

With the cross of Jesus going on before.

Christ, the royal Master, leads against the foe;

Forward into battle see His banners go!

Refrain

Onward, Christian soldiers, marching as to war,

With the cross of Jesus going on before.

Lyrics, Sabine Baring-Gould, music, Arthur S. Sullivan.

It was Brother Edwin who had taught me that one of the most important sacraments of the Catholic Church was the almost forgotten one (it used to happen between Baptism and First Communion) called Confirmation. This sacrament girded the recipient as a metaphorical soldier of Christ. Not as one that would climb up on a war horse and swing a broad sword at Moors in Spain but as one who would defend one’s faith by knowledge of it. The knowledge would help explain and perhaps even entice that curious nonbeliever to join. For years when people asked I could explain such comlicated stuff as transubstatiation, the Holy Trinity and the misunderstood concept (and doctrine) of Ex-cathedra. I felt happy in being able to explain and I never had the intention to convert anybody.

The first seeds of doubt began when my friend John Straney in our 11th grade at St. Ed's paraded his nonbelief in the existence of God in a most vocal manner. The Brothers of the Holy Cross in our Catholic school used General MacArthur tactics and simply moved around him and let him wither in isolation. They never made it an issue. I would have thought that they would have expelled him. Straney graduated just like the rest of us. I remember trying to reason with him and using the so-called proofs of the existence of God taught us by Brother Edwin. I tried Aristotle’s unmoved mover but Straney was not fazed by the human tendency to reject infinite infinities which can be so problematic to most of us. “Why does there have to be a beginning,” he would counter my arguments. “Why cannot time be a circle?” he would suggest.

In the late 60s and early 70s my mother had terrible vertigo Ménière's and she was no longer able to play her piano and she could no hear us most of the time because of the constant buzzing in her ears. The vertigo was terrible. I have suffered motion sickness most of my life and I can attest to her belief that pain was more bearable than vertigo.

My mother began to bitterly tell me she did not believe in a God that cared or a God that participated in human affairs. “I have lost my belief in the power of prayer. He does not listen. He is not interested.” Suddenly all my Catholic education did not help me in countering my mother’s journey into despair. This despair reminded me of Graham Greene's own Scobie in his Heart of the Matter. I was helpless until she died in the early 70s. It almost seemed that we had been living in that strange area that Graham Greene scholars often called Greeneland. It was an area populated by doubt about one's beliefs.

When theologians and others were arguing about the ultimate fate of Scobie in The Heart of the Matter, Graham Greene commented:

"I wrote a book about a man who goes to hell -- Brighton Rock -- another about a man who goes to heaven -- The Power and the Glory. Now I’ve simply written one about a man who goes to purgatory. I don’t see what all the fuss is about" (Time, October 29, 1951, p. 103).

The 1966 issue of Time, Is God Dead? had put those seeds of doubt in my head. In the 60s I read Time every week. It was my bible.

"Have I complete belief?" Sancho asked. "Sometimes I wonder. The ghost of my professor [Unamuno]haunts me. I dream I am sitting in his lecture room and he is reading to us from one of his own books. I hear him saying, 'There is a muffled voice, a voice of uncertainty which whispers in the ears of the believer. Who knows? Without this uncertainty how could we live?'"

Monsignor Quixote, Graham Greene, 1982, Simon and Schuster, New York.

A few months ago as Abraham Rogatnick was slipping away at VGH we discussed for hours our mutual shared belief in the nothingness that awaits. I read to Rogatnick Ambrose Bierce’s wonderful and poignant story of the man who does not fear death until it is suddenly confronts him, Parker Adderson Philosopher. We discussed Epicurus’ logical reasons for not fearing death.

Now as I look back at my evenings and days with Rogatnick I understand why Sancho’s comment on complexity and the Bishop of Motopo’s statement, that we need mysteries to have faith, is so important. That is what is missing in my life. The complexity and mystery of my willfully suppressed Catholic faith have not been replaced by any equivalents. I tell my students that even if you are not religious you must have some knowledge of religion (and in particular the Roman Catholic one) in order to tap into the stories of the saints, the mysteries, the accounts in the bible (both the Old and the New) to find inspiration for photography. After all it was the Catholic faith that gave us soaring cathedrals, soaring Bach cantatas and Masses, El Greco, Raphael and Leonardo.

Somehow the complexity of Ruby, Leopard, HTML and XML cannot replace the mystery and complexity of the faith that I once had. The former codes may be complicated but they don't have the challenge of an unsolvable and unresolvable unknown that will always be rooted in faith. Of what use is Twitter and Facebook and how do these social networks operate? The answer is much too complext for me and the question itself does not interest me. Have I underrated faith for so long?

My eldest daughter Ale (41) was the last member of our family to go to catechism and have a traditional First Communion. This happened around 1974 in Mexico City before we came to Vancouver. Because Ale has kept her connection with her Mexican friends she has a pretty good idea of some aspects of Catholicism that my youngest daughter Hilary (38) lacks. When my mother died in 1973 all semblance of a religious education for her granddaughters stopped.

My Argentine relatives like many Argentines are devout practicing Catholics. One of my nephews is a member of the Opus Dei. When Rosemary, Rebecca and I went to Buenos Aires in 2004 I made it a point to go to mass with my first cousin and godmother, Inesita O’Reilly. I thought it would please her. We brought Rebecca along who thought the Mass was most entertaining. She kept waving at the extremely handsome and young priest. We did our best (between us) to explain to her what she was seeing. For me there was the satisfying symmetricity of Rebecca being in a church to which I had attended many a time as a young boy. It was at La Redonda (so called as the church is a miniature version of Rome’s round Pantheon), that I had pushed my own idea of what was proper in my faith. I had arrived late (with all the intentions) when the Offertory began. According to my confessor if I arrived late at Sunday Mass but got to the Offertory that was considered a full Mass. I never told him that this was not an accidental lateness. As soon as the priest said itte Missa est (Latin for go, the Mass is ended in the traditional Tridentine Mass) I was out of there. Because of the Buenos Aires heat I would usually be outside the church’s doors looking into the Mass. I often wondered if going to Mass involved being physically in the church!

When we took Rebecca three times to Mexico (Guanajuato, Morelia and Mérida) we went to see lots of churches (the picture here is of Rebecca at the Jesuit church in Mérida). Rebecca wanted to know what saint was where and she wanted me to explain the paintings. Being a baptized Christian who was Confirmed I could give her the explanations. She is now able to explain each station of the cross as I have had to tell her the story every since I started taking her to the Pacific Baroque Concerts at St James Anglican. Rebecca knows that this Vancouver Anglican church is about as Catholic as it can be without being so.

Rebecca can believe (or not) in whatever she wants and that’s up to her busy parents to deal with. But when I am with her I can at least explain to her those mysteries, those complex mysteries that make life and an appreciation of the arts that much more challenging and fun.

I started something last Saturday. I threw a fork on to the kitchen floor. I watched Rebecca as she saw me do it. I asked her later how the fork had gotten there. She correctly told me I had dropped it. From there we went to discuss how any movement or change precludes a mover or changer. At the table I asked her in the presence of her mother, “Rebecca what comes to mind when you see a fork on the kitchen floor?” She answered, “It takes me to the concept of Aristotle's unmoved mover.” "And who or what is the unmoved mover?”

She answered, “God."

I do hope my life will get more complicated again.

Graham Greene On Sharks, Vultures and Palenque

Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam