A Penguin In The Arctic - Take Two

Thursday, April 28, 2011

|

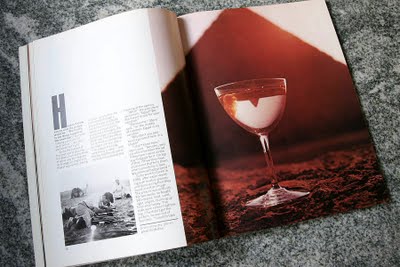

| Vancouver Magazine Jan/Feb 2011 |

Generally when I teach my class at Focal Point, after a studio session, (when my students shoot under my supervision) there is a critique in the next class. Students bring the pictures they took in the all-day studio session and we project them so that we can discuss, gently, what is good and what can be improved. This year I just finished a course called Editorial Photography. The final critique was a couple of weeks ago and suddenly, by some strange planning oversight, I am to give my class one more peek into the world of magazines today. How does one teach such a class when magazines and newspapers (that used to pay good bucks for the content and did so to me!) are in decline and the mantra of our age is that the best price is free?

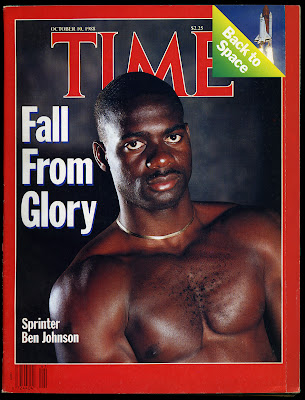

The first picture here is a Polaroid self portrait that was used by the kind folks at Vancouver Magazine who hired a writer, the best in the business, Charles Campbell, to write about me before I fade, not like an old soldier, but like an old poorly fixed photograph. The article had nine pages of pictures! It was on the newstand from late December until the end of February. I was truly surprised to have received exactly one phone call in all that time. I had not even expected one. I do believe that the importance of magazines has shifted to the web. In the second picture is my photograph of sprinter Ben Johnson. Time paid me a ton of money for that. It would be difficult for me to imagine getting that kind of money now. I have a sobering respect for anybody who wants to be a photographer in today's climate.

For a while I would tell my students that if they wanted to be photographers they might want to have a plan B, such as the much more lucrative profession of plumbing. But if I were loud and clear on this these institutions of the photographic arts would not be clamoring to give me a voice in class.

I found a handle, a very positive one, that follows the history of photography from its inception around 1826 and how this brilliant and accurate new “thing” was limited to appearing on salon walls or individually inserted in books as Henry Fox Talbot did with his photogenic drawings published in six installments as the Pencil of Nature. This book happens to be the world’s first (and still one of the most expensive) illustrated “coffee table” book. These pictures could not have been printed directly into books as nobody had invented a system for doing so. American Civil War photographers had to see their pictures converted to wood cuts before they could appear in newspapers or in such journals as Harper’s Weekly.

But around 1877 a newspaper in New York City published a photograph of the Steinway (about the arts!) Building using a new technique called halftone reproduction. From then on the photograph was king and it could appear on anything and it could even be sent by wire across the world (long before the sending of digital files through the internet).

|

| My first & last Time Cover, Oct. 1988 |

I tell my students in as positive a manner as I can (and I never mention the plumbing angle) that photography is now in a transition between the halftone and whatever will emerge in our digital age. What the world will do for them and what they can do for that world is for the world and my students to decide. I can only now, at my age, just watch.

I felt that a blog that I published (even now that sounds hollow to me when considered in the context of placing something on the web) back in December 2009 might be appropriate for my students to consider in their last class today.

It is a brave new world, but an uncertain one, they stand to inherit.

A Penguin In The Arctic

Friday, December 04, 2009

In the early 50s Bert Stern, 17, was working in the mailroom of Look Magazine. Delivering letters to the art director of the magazine’s promotion department he looked at a layout and blurted, “There’s a better way to do that.”

“Okay,” the amused art director told the upstart boy with no college, no designing training, “so do it.” Stern had found a teacher. The man’s name was Hershel Bramson. He hauled Stern up from his mailroom work to work as his assistant. Often the two would shut Bramson’s door to talk over a Coke and a handful of Oreo cookies; listening, cutting and pasting, Stern absorbed the elements of design that he now brings to every picture. “If you are going to put something on a very nice piece of clean paper,” Bramson used to tell him, “improve it. Don’t schlock it up.”

In 1955 under contract with Smirnoff Vodka Stern took an idea to the ad agency L.C. Gumbiner on how to convey the driest of martinis.

“What!”the president exclaimed. “Egypt? We don’t want to pay for your vacation.”

“Believe me, “Stern said, “in the middle of summer, Egypt is no vacation.”

“Why don’t you just build a pyramid here in a studio?”

“I don’t know how,” Stern said. “Besides, people will remember the ad if they hear I went all the way to Egypt for it. On top of that, they have an instinct that tells them when something is fake. We all know that pyramid.”

Petersen’s Masters of Contemporary Photography

Bert Stern: How To Turn Ideas Into Images

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Since the late 70s when I first purchased the above book about Bert Stern, I have been inspired by all of Stern’s principles for conceptualizing ideas in his head that lead to memorable images.

But I also worry about Stern’s belief in people having an instinct for what is real and for what is fake. Stern’s shot of the ultimate dry martini had the impact that could only happen in a "pre-special effects/Photoshop" era. Now just about anybody can seamlessly place a penguin in the arctic and a polar bear in the Antarctic. Nothing is seen as impossible anymore.

While I never went to Egypt or spent 2 weeks and 140 degree heat on the desert sand I have my own photograph that today would certainly not be conceived and achieved in the same way.

It was sometime in the late 80s that Vancouver Magazine editor Malcolm Parry told me (it was a precise and startling mouthful), “Alex I want you to photograph a Porsche Carrera 4 and a Nissan 300ZX together and moving. I want you to use that Norman flash of yours. I want the cars to be red and I want you to be in one of the cars. I will drive the other.”

I thought Parry was crazy. Why the flash? Was there any purpose in it except to make my task that much more difficult? The startling glow of the resulting picture says something about Parry's talent for pre-visualization.

The first thing I did was to inspect both cars. It was our luck that the dealers had a red Porsche and a red Nissan. The 300ZX’s front end was all plastic. But the Porsche’s had a metal hook for towing it. I could design some sort of clamp that would hold a motorized Nikon FM-2 and Norman 200B light head and battery pack. I needed an extension to make the motor drive cord from the Nikon extend all the way to the interior of the car where I would be riding shotgun. I told Mac that the only way I could get the shot was to buy an expensive Nikon fisheye lens. I purchased a used one and Vancouver Magazine footed the bill.

For close to an hour we went up and down Georgia and the Cambie Street Bridge. We had problems with drivers that would position their cars so as to block my shooting angle. Sometime in the end of the day we had one of those dramatic skies and I got my shot.

Both the shots you see here have no manipulation except the manipulation of neurons in the mind. What will replace that, now that we can put penguins in the arctic and polar bears in the Antarctic?