A Death In Venice

Thursday, March 19, 2009

Venice has been painted and described many thousands of times, and of all the cities of the world it is the easiest to visit without going there.

Italian Hours, Henry James

‘I'm starving,’ she said. ‘I’ll put the pasta water on.’

Zen followed her out to the kitchen. On the table a stoppered litre bottle of red wine, a packet of spaghetti, a fat clove of purple-skinned garlic, a small jar of oil which was the opaque green of bottle glass abraded by the sea, and a twist of paper containing three wrinkled chillis the colour of dried blood.

‘Aglio, olio e peperoncino,’ he said.

‘I told you it was nothing fancy.’

Dead Lagoon, Michael Dibdin

Rosemary and I sat in the den for lunch yesterday. I had made a gruyere, ham and fresh tomato omelette. Rosemary turned on the TV. My large plate felt hot on my lap. We will not admit to the realization that we sometimes watch TV while eating and we will not acknowledge this culinary aberration by resorting to a TV dinner tray. On CNN I saw that picture of Natasha Richardson and her husband Liam Neeson. It seems it’s the only image the media could rustle up in our age of the all-knowing and all seeing image bank, Getty or Corbis. I got up.

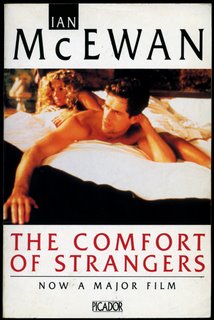

I went to a corner in the den where I had piled some books in a recent rearranging of my library. It was a pile of softcover books. From the pile I retrieved Ian McEwan’s second novel (1982) The Comfort of Strangers and I showed it to Rosemary. “Here is the Natasha Richardson they are talking about.” I had also seen this great little movie. The novel does not ever state nor confirm the reader’s suspicion that the novel is set in Venice.

For Mary the hard mattress, the unaccustomed heat, the barely explored city were combining to set loose in her a turmoil of noisy, argumentative dreams which, she complained, numbed her waking hours; and the fine old churches, the altar-pieces, the stone bridges over the canals, fell dully on her retina, as on a distant screen.

The film directed by Paul Schrader is firmly set in Venice. The only other film on Venice with the same pull on my memory, as good, scary and strange as Schrader's was Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now. The film was based on a Daphne du Maurier story, and cast Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland. The Comfort Of Strangers boasted an unusually excellent cast, Natasha Richardson, Rupert Everrett, Christopher Walken and Helen Mirren. Harold Pinter’s screenplay is the creamy icing on the cake.

In McEwan's 1990 novel The Innocent a man cuts up a body and quietly and calmly fits it into a suitcase. The almost unemotional McEwan style forces me to read his books in one sitting but not often. They are so cold and uninviting. The Comfort of Strangers is such a film. It is a film you can only see once even if you never forget it. In spite of the colourful Venice it is cold and gothic. But not as scary as the novella of the same name:

While they were out, and not only in the mornings, a maid came and tidied the beds, or removed the sheets, if she thought that was necessary. Unused to hotel life, they were inhibited by this intimacy with a stranger they rarely saw. The maid took away used paper tissues, she lined up their shoes in the cupboard in a tidy row, she folded their dirty clothes into a neat pile on a chair and arranged loose change into little stacks along the bedside table.

Rapidly, however, they came to depend on her and grew lazy with their possessions. They became incapable of looking after one another, incapable in this heat, of plumping their own pillows, or of bending down to retrieve a dropped towel. At the same time they had become less tolerant of disorder. One late morning they returned to their room to find it as they had left it, simply uninhabitable, and they had no choice but to go out again and wait until it had been dealt with.

Near the end of the novella McEwan writes:

‘Very well,’ Robert said and reached Colin’s arm, and turned his palms upward. ‘See how easy,’ he said, perhaps to himself, as he drew the razor lightly, almost, playfully, across Colin’s wrist, opening wide the artery. His armed jerked forward, and the rope he cast, orange in this light, fell short of Mary’s lap by several inches.

After I saw the film, Natasha Richardson was indelibly engraved in my brain as Mary in The Comfort of Stranger’s Colin and Mary and with two other films featuring pairs, Peter Yates’ 1969, John and Mary (Dustin Hoffman and Mia Farrow) and Frank Perry’s 1962 David and Lisa with Keir Dullea and Janet Margolin.

On further thought of the death of Natasha Richardson I scoured my library and found quite a few books on Venice. There are many more than I show here as I have all of Donna Leon’s Commisario Brunetti, all eight of them.

It was not too long ago that I decided to read a pocket book I used to prop up a bookcase. The cover was so terrible I decided the book was not worth reading. I can report that if I were to read it again perhaps my melancholy over the death of Mary (Natasha Richardson) might be dispelled just a bit.

But that will not happen. I will probably re read the best Venice novel in my library, Michael Dibdin's Aurelio Zen police procedural, Dead Lagoon. Set in a freezing Venetian winter it is gloomy and depressing. I can feel the decay of Aurelio Zen's city of birth in shivers during every reading. I have begun to understand that Henry James was correct. On the other hand I will have to correct my oversight in not having yet read Thomas Mann's Death in Venice.

And no Natasha Richardson did not die in Venice. It was in Manhattan but my memory of her will always live and die in Venice.