The warning message arrived on Monday, the bomb itself on Wednesday. It became a busy week.

The Care of Time, 1981, Eric Ambler

Last Tuesday I went to Focal Point to teach my perennial class The Contemporary Portrait Nude. I decided to take the B-Line bus which drops me off half a block from the school on 10th Avenue. The stop is right by a used books store. I always look in the window. I immediately noticed the Eric Ambler novel (sometimes called political thrillers), The Care of Time. I knew I was going to buy it for two reasons. I read any book by the English author who died in 1998 because he was my mother's favourite thriller writer. I may have been 15 when she handed me a copy of his A Coffin For Dimitrios. I re read it every few years it is that good. It begins:

A Frenchman named Chamfort, who should have known better, once said that chance was a nickname for Providence.

A Coffin for Dimitrios paved the way for my later appreciation of Ian Fleming, Len Deighton, John Le Carré and Graham Greene (in particular The Confidential Agent). The second and most important reason is that here was a novel by Ambler that I had not read. I opened the book and read the first incredible paragraph (above). I paid $4 for a first edition which is in reasonable shape. The photograph (seen here) of the author by photographer Stephen Cornwell graces the back cover.

This novel, about a ghost writer who has a good reason to dislike both the CIA and the Iraquis, has a relevance today. Consider the second paragraph:

The message came in an ordinary business envelope that had been mailed from New York but had no return address on it. Inside, folded in three, was one of those outsize picture postcards that are offered to tourists in some places nowadays. This one was of a hotel with palm trees and carried an ornate caption proclaiming that it was the Hotel Mansour, Baghdad, Republic of Iraq.

Yesterday afternoon I visited my friend, photographer Raymond Lum. As a graduate from LA's Art Center he is very much like all the other graduates of Art Center that I have met. This means that Ray is most concerned with accuracy and perfection. With the advent of digital photography the pictures on his monitor have no hint of colours that were not in the original scene that he saw before he photographed it. His portraits have neutral gray backgrounds, blue shirts are blue with no hint of purple and skin tones are real enough to almost be uncanny.

Ray made an uncharacteristic mistake when he told me, "The difference between shooting RAW and a jpg (two different methods of storing the information of a digital photograph) is that RAW images have richer colour." As I admired Ray's realistic portrait of a real estate agent (Plato might have called it an essence of the real estate agent) I answered back, "Ray, I like your portrait because it is accurate. I am not interested in richer colour. I am interested in accuracy." One of the reasons Ray gets this accuracy is that he does not depend on a DSLR (digital single lens reflex) but has a scanning back attached to his Hasselblad. The pristine image of the real estate agent is a whopping 20 megabytes.

Looking at Ray's accurate portraits (he spends a considerable amount of money and much effort in making sure his top-of-the-line LED monitor is calibrated to his specifications at least once a month. Any picture that you see on his screen and one that he prints on his inkjet printer are virtually identical), I thought of the Acoustic Research ads of the early 60s that advertised a unique approach to sound. AR conducted a series of over 75 live vs. recorded demonstrations throughout the U.S. in which the sound of a live string quartet (The Fine Arts Quartet) was alternated with echo-free recorded music played through a pair of AR-3s. In this “ultimate” subjective test of audio quality, the listeners were largely unable to detect the switchovers from live to recorded, a strong testament to Acoustic Research audio quality. This was in an era before we began to boost bass, zing the higher frequencies and surround ourselves with sound or hear it inside our head from a little machine in our front pocket. A sense of loss in the original quality of sound has many an iPod owner docking the device into a tube amplifier that is supposed to uncompress the sound and return the original presence taken out during compression.

By the 80s, sound enhancement concepts had wandered off into the realm of photography. Film was made with punchy colours and increased contrast. There was slide film that gave people an artificial sun tan. It was advertised as having a warmer and rich colour. I had an admiration for the colour carbro process nude prints by Paul Outerbridge taken in the late 30s and 40s. Skin looked real. Instead of this accuracy we were fed high contrast and gloss by Cybachrome technology.

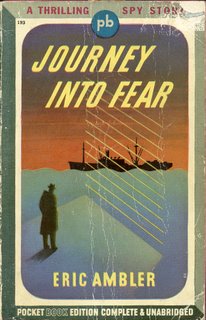

From his first 1936 novel The Dark Frontier to his 1991 Waiting for Orders Ambler wrote cool thrillers in which most of his protagonists were ordinary (in some cases colourless) people who more often than not accidentally got involved in situations that were completely beyond their control. One such man is Charles Latimer a lecturer in political economy who writes his first detective novel at age 35, called A Bloody Shovel. Latimer is the main protagonist of A Coffin for Dimitrios whose life changes when he meets (in Istanbul, naturally!) one of the most interesting and complex characters in thriller writing, Colonel Haki. The suave Colonel tells Latimer:

"I get all the latest romans policiers sent to me from Paris," he went on. "I read nothing but romans policiers. I would like you to see my collection. Especially I like the English and American ones. Al the best of them are translated into French. French writers themselves, I do not find sympathetic. French culture is not such as can produce a roman policier of the first order. I have just added your Une Pelle Ensanglantée to my library. Formidable! But I cannot quite understand the significance of the title." Latimer spent some time trying to explain in French the meaning of "to call a spade a bloody shovel" and to translate the play on words which had given (to those readers with suitable minds) the essential clue to the murderer's identity in the very title.

Much has been written on the excellence and richness of Patrick O'Brian's nautical novels. I, too have found them excellent and I have read the series twice. But this does not mean that I will forgo the enjoyment of C.S. Forrester's Hornblower novels. I find a telling connection between Forrester's Hornblower and Ambler's everyday men who rise to become heroes. I see a further link between Acoustic Research's (and Angel Records) penchant for accuracy and Raymond Lum's near obsession with the accuracy and neutrality of colour in his photographs.

It is almost impossible to understand what is in Hornblower's mind at any time because Forrester choses not to tell us. He does not colour or enrich the man with deep thought. It is there, but between the lines. The reader has to extract it. It is for this reason that Gregory Peck's performance as Hornblower is so perfect. We have to imagine everything in a glance or a pressing of lips. Ambler's description of Colonel Haki seems to be matter of fact but beneath it all is a man who is complex and scary. And much the scarier as we weigh him in our imagination.

I tell my students at Focal Point that unlike film photographers (as this one) they now have the power to record and display the colour and subtlety of human skin with a near perfection that was never there until now. So few of them take advantage or understand the gift they have.

Thankfully there are a few out there (Raymond Lum is one of them) who like Ambler, Forrester, and my Acoustic Research amplifier provide me with the richness (pardon me!) and the enjoyment of that which is plain and accurate.

The man standing in the shadow of the doorway turned up the collar of his overcoat and stamped his numb feet gently on the damp stones.

First paragraph, Cause For Alarm, 1945, Eric Ambler