Clocks - Hourglasses, Watches & Rosemary

Saturday, February 05, 2022

| Rosemary - Mexico City -1968

|

I remember back when I did not know what a computer virus

was. It was 1994. I first learned it by my then friend William Gibson. He also

told me that he liked Apple computers because they used ikons. I had no idea

what he meant. He also told me in those early days of the internet when my

email was [email protected] that there

was something called Altavista and that it was a search engine. By then I was

using my Rosemary’s office IBC Thinkpad (remember them?)

Now in this century I could not possibly think of reading

in bed without Google access with my phone. I can look up obscure words

immediately.

I also use Google when I want to mate (combine a photo or

photos of mine with some poem or article or book by an author that I like. I

have used Google to find over 75 Emily Dickinson poems that fit my photographs

by simply putting fall, Emily Dickinson or death, Emily Dickinson.

I have a friend, Ian Bateson who likes to use a certain word

and expression that he knows annoys me. This is, “Alex you are reiterating

yourself." That hit home today when I spotted two photographs I took of Rosemary

in 1968. In one she is with an hour

glass and in the other I added a very large alarm clock.

I went to Google and put reloj, Jorge Luís Borges. I sort of

knew what I would find. It was his lovely poem on an hour glass called El reloj de arena. But I was most surprised when the second Goggle hit was this::

El Reloj de Arena - The Hour Glass - Jorge Luís Borges What to do? I have decided to link that original blog and add

something new. I have re-scanned the two negatives so they will look better.

But I will also include here an essay I know all about by Julio Cortázar. One

part is the preamble and the other is the actual instructions on how to wind a

watch. Both are below in Spanish and in English. Cortázar had a very dry and unusual sense of humour. He wrote several of these odd little essays. Two are are blogs of mine. One is on how to go up stairs and the other how to go up stairs backwards.

Some who may have gotten this far might object that a wrist

watch has nothing to do with an hour glass or a gigantic alarm clock. Any excuse to put up pictures of my Rosemary is enough

justification for me. Preámbulo

a las instrucciones para dar cuerda al reloj. Julio Cortázar Preamble to the instructions for winding the watch.

Piensa

en esto: cuando te regalan un reloj te regalan un pequeño infierno florido, una

cadena de rosas, un calabozo de aire. No te dan solamente el reloj, que los

cumplas muy felices y sí esperamos que te dure porque es de buena marca, suizo

con áncora de rubíes; no te regalan solamente ese menudo picapedrero que te

atarás a la muñeca y pasearás contigo.

Think about this: when someone gives you a watch as a

gift, they give you a flowery little hell, a chain made of roses, a prison cell

made of air. They do not give you just a watch, may you have a happy birthday

and, yes, we hope it lasts you because it’s a good brand, Swiss with a ruby

clasp; they do not give you just that minute piece of stonework that you will

tie to your wrist and carry around with you.

Te regalan -no lo saben, lo terrible es que no lo saben-,

te regalan un nuevo pedazo frágil y precario de ti mismo, algo que es tuyo pero

no es tu cuerpo, que hay que atar a tu cuerpo con su correa como un bracito

desesperado colgándose de tu muñeca. Te regalan la necesidad de darle cuerda todos los días, la obligación de

darle cuerda para que siga siendo un reloj; te regalan la obsesión de atender a

la hora exacta en las vitrinas de las joyerías, en el anuncio por la radio, en

el servicio telefónico.

They give you – they don’t know it, the terrible thing is

that they don’t know it – they give you a fragile and precarious new piece of

yourself, something that is yours but is not your body, that you have to tie to

your body with your strap like a hopeless little arm hanging itself from your

wrist. They give you the need to wind it every day, the obligation to wind it

so that it keeps on being a watch; they give you an obsessive need to pay

attention to the exact hour in the shop windows of jewelers, in the commercial

on the radio, in the phone service. Te

regalan el miedo de perderlo, de que te lo roben, de que se te caiga al suelo y

se te rompa. Te regalan su marca, y la seguridad de que es una marca mejor que

las otras, te regalan la tendencia de comparar tu reloj con los demás relojes.

No te regalan un reloj, tú eres el regalado, a ti te ofrecen para el cumpleaños

del reloj.

The give you the fear that you might lose it, that it

might be stolen from you, that it might fall to the floor and break. They give

you its brand, and the certainty that it is a better brand than the others,

they give you the tendency to compare your watch with other watches. They don’t

give you a watch, you are the one given as a gift, they offer you yourself for

the watch’s birthday. Instructions on how to wind a watch - Julio Cortázar (in Spanish and English) Instrucciones

para dar cuerda al reloj

Allá al

fondo está la muerte, pero no tenga miedo. Sujete el reloj con una mano, tome

con dos dedos la llave de la cuerda, remóntela suavemente. Ahora se abre otro

plazo, los árboles despliegan sus hojas, las barcas corren regatas, el tiempo

como un abanico se va llenando de sí mismo y de él brotan el aire, las brisas

de la tierra, la sombra de una mujer, el perfume del pan.

¿Qué más

quiere, qué más quiere? Átelo pronto a su muñeca, déjelo latir en libertad,

imítelo anhelante. El miedo herrumbra las áncoras, cada cosa que pudo

alcanzarse y fue olvidada va corroyendo las venas del reloj, gangrenando la

fría sangre de sus rubíes. Y allá en el fondo está la muerte si no corremos y

llegamos antes y comprendemos que ya no importa.

There at the corner is death, but do not be afraid. Put

on the watch with one hand, with two fingers go to the winding knob, turn it

gently. Now there is a different stage, trees display their leaves, ships run

in regattas, time like a fan fills itself with its being and from it air

emerges, the earth’s breezes, the shadow of a woman, the perfume of bread.

What more do you want, what more do you want? Fasten it

immediately to your wrist, give it liberty to tick, imitate it with longing.

Fear rusts the anchors, everything that was found was forgotten and has

corroded the watch’s veins, gangrene sets in on the cold blood of the rubies.

And there at the end is death if we do not run and arrive and understand it is

no longer important.

My translation

At Odds with Jorge Luís Borges & una canadiense

Friday, February 04, 2022

| | Rosemary in Chapultepec Park 1968 |

Living in

Buenos Aires as a little boy my knowledge of Canada was next to zero.

My

grandmother would tell me the story on how when she became a widow in 1918 and because she was of a patrician family she could not find a job. She and her son and two daughters took a Japanese ship to a place with mountains

and trees called Van-koo-ver. At the train station (it must have been the CP Train

Station) they boarded a train to Montreal and from there to New York City where

they settled in the Bronx

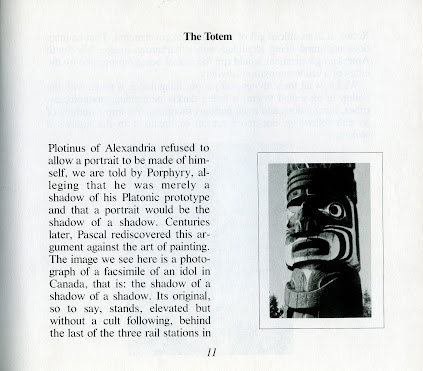

It wasn’t

until my return to Buenos Aires in 1965 to do my military service in the

Argentine Navy that at the Retiro Train Station I spotted a curious structure.

It was a Canadian totem pole that had been erected the year before. It seems the Canadian government had sent it to

Argentina as a gift.

In my Jorge

Luís Borges – Atlas (1985 translation in English from 1984 book in Spanish) I

have always known how Borges had no liking for Indigenous culture of any kind.

He preferred Milton and Shakespeare.

I have

found out that the original totem deteriorated and it was removed in 2008 and

replaced by a new one in 2012.

When I left

Buenos Aires to my home in Veracruz, Mexico in 1967 in an Argentine merchant

marine ship (ELMA) called the Río Aguapey I was unaware that the Victory Ship

that it was, had been built at the Burrard Shipyard in North Vancouver.

In the

latter part of 1967 I met Rosemary Healey who told me all about a man called

Pierre Trudeau and of a lovely city she pronounced as Kebec. I fell for her

blonde hair, her legs and married her. With our two Mexican-born daughters we

drove our VW to Vancouver in 1975. I have been a Canadian Citizen for many

years.

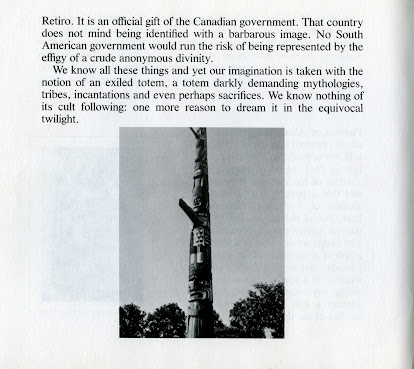

It is

paradoxical that the first totem Rosemary ever saw was one in Chapultepec Park

in Mexico City. Until yesterday I had not known that I had photographed

her by the totem not only in b+w but in

colour. A year ago when I finally finished Julio Cortázar's Rayuela, from front to back, and then to all of his recommended variations, I discovered that in wintry Paris he wore a plaid, flannel shirt that he called una canadiense.

As for

Borges. I like Milton and Shakespeare but I also admire and respect Indigenous

culture, too. He was a man of that other century and I am doing my best to be

one of this one.

Susan Musgrave - Formless, as the divine

Thursday, February 03, 2022

| Susan and Stephen - October 12 1986

|

When I sent poet Susan Musgrave my blog on poetry, Poetic Justice , she and I discussed the grief of a loss. In her case it was about the

recent death, September 14 2021, of her 32 year-old daughter Sophie, and, in mine the loss of my

Rosemary on December 9 2020.

While I am not a poet I find a measure of relief in writing

about grief and in reading poetry. That she sent me the recent poem she wrote of Sophie, I consider not only an honor but it also does provide me with a measure of escape from my own loss by sharing someone else's. And she sent me a poet's advice: Oh, I am so sorry to hear of Rosemary's death, Alex. 52 years. Joan

Didion's books — her husband's death and her daughter's — are bibles of

grief. Julian Barnes has some beautiful books about his wife's death — Levels of Life (the third section) and of course C.S. Lewis. A Grief Observed.

Of her daughter she wrote:

My daughter, Sophie (Stephen's daughter) died of a

Fentynal and Benzos overdose on September 8, 2021, in Vernon. She went off her

Suboxone, cold turkey, in late August and then started using Fentanyl to stop

from getting sick.

She was found on the 4th without a pulse or heartbeat.

They revived her using CPR for an hour, but there was too much damage to her

brain and kidneys. I brought her ashes home to be with Stephen's. Sophie was

32.

I never knew such pain existed. There hasn't been a day

since then that I haven't wept. Sometimes for hours at a time. I wrote this for

her on the plane flying home.

September 14, 2021

For Sophie Alexandra Musgrave Reid (January 4,

1989-September 8, 2021)

“The

reckless seek death the way the poets seek rhyme, the patient

a cure,

the prisoner freedom.”

—

Rumi, The Fire of Love

The day you are cremated a girl modeling

a black hoodie,

like the one I’ve chosen for you to wear, lights

up my Facebook page:

I survived because the fire inside me burned

brighter than the fire

around me.

I hear you laugh at the irony as

they fire up the retort,

a laugh dragged through the ashes of a

thousand cigarettes, tokes

of crack, my sweet dangerous reckless

girl, what could I do

but weep, the way I did when you were four,

butting out

a Popeye

candy cigarette you scored from the

boy next

door

for

showing him your vagina through the split

cedar

fence.

I told

you, next time, baby, hold out for a

whole

pack, trying

to be

brave, the way only a mother could. Now

I carry

you home

in a

plain cedar urn, the remains of all you

once

were reduced

to this

smaller, portable size. Not even you

would

survive

the fire

this time, your light in ashes now,

formless,

as the divine.

Monica Vitti - Rome, 3 November 1931 - Rome, 2 February 2022

Wednesday, February 02, 2022

| Monica Vitti - Bert Stern

|

Because I am a remnant being from that past 20th century it is understandable that I eschew most of the films made in this century.

I was raised by my mother to appreciate the likes of Leslie

Howard, Ronald Colman. Katherine Hepburn and Jean Simmons. It was only when we moved to Mexico

City from Buenos Aires in 1954 that I saw Mogambo and fell for Grace Kelly.

While in Buenos Aires my father often took me to see movies

on Lavalle which was a street with shoulder to shoulder movie houses for at

least three blocks. We saw swashbucklers, war movies and films which we

Argentines called de conboys.

In short my level of film sophistication and sophistication

of any other kind was low. My grandmother had given me subscriptions to

Selecciones del Reader’s Digest and Mecánica Popular.

When I returned in 1965 to do my military service in the

Argentine Navy I met two women who became my girlfriends. The first one, Uruguayan-born

Corina Poore, introduced me to the music of Bob Dylan, Joan Baez and Peter, Paul & Mary.

She had a lovely voice and played her guitar very well.

My second girlfriend, Susana Bornstein was much more

critical of my lack of sophistication. She invited me to the Teatro Colón where I

saw my first two operas, Prokofiev’s The Fiery Angel, and Gluck’s Orphée et Eurydice.

If that wasn’t enough she took me to see the Beatles in Help! and the

eye-opener Japanese film The Woman in the Dunes. But my level of sophistication

did not rise to her liking and one grim Buenos Aires winter afternoon she called me to

tell me that I had no future, that I was not to call her ever again and that

she was leaving me for a violinist of the Teatro Colón Orchestra.

There was one glimmer of hope for me as I had discovered

Astor Piazzolla in 1965 and had attended a concert with Susana. I wrote about

that here.

Once I returned to Mexico City in 1967 (before I was to

meet my Rosemary Healey) I was under the wing of Raúl Guerrero Montemayor who

taught me how to teach English and with his multiple languages made me curious.

He helped by taking me to films I had no idea existed. These were the three

films of Michelangelo Antonioni, L'Avventura, La Notte and L'Eclisse. They introduced me to the freckles and other wonders of Monica Vitti. By

the time I saw Antonioni’s Blow-up he was part of my new sophisticated radar.

I believe that it was Monica Vitti who gave me the

ability to appreciate Charlote Rampling and Molly Parker.

Vitti also made me understand the beauty of seeing a film in

a foreign language (not dubbed). By the time my Rosemary saw all the Italian

series Montalbano we could both comprehend most of the Italian being spoken.

I do not believe that there are many actresses (I am

old-fashioned) that now are at the level of intensity that Monica Vitti had. And in my 52 marriage to Rosemary we attended concerts, theatre, dance and shared many books with mutual pleasure. I would assert that she helped me reach my considerable (in my eyes) level of sophistication.

|