|

| Harpsichordist Michael Jarvis Illustration by Lauren Stewart & Graham Walker |

On Saturday my friend the graphic designer Graham Walker my 10-year-old granddaughter Lauren Stewart (on her own accord she asked her mother for violin lessons almost a year ago and has been practicing daily since) and I went to a Pacific Baroque Concert at St. Mark’s Church. The orchestra had its former artistic director, violinist Marc Destrubé as its guest leader. The PBO’s regular leader, harpsichordist and organist Alex Weimann had previous commitments.

The concert was called Purcell & Friends and I must say that after an enjoyable evening I must add that Purcell’s friends Matthew Locke and Thomas Baltzar weren’t the only friends around. Having followed the Pacific Baroque Orchestra since its founding (by Destrubé) in 1991 I include the members of the orchestra as my friends. To be able to hear this kind of music live and in Vancouver puts our city in a position of exclusivity. And to sit so near and to listen to friends (virtuoso, but friends nonetheless) play is a pleasure for which I feel most guilty. More should enjoy this if they only knew.

Because the baroque repertoire of late now includes composers previously unknown (consider that J.S. Bach was forgotten until Felix Mendelsshon directed a performance of the St Matthew's Passion in 1829) the music is as fresh today as it was when it was first played. It was new music then. Destrubé likes to point out that it is new music today.

My mother was an unusually good pianist and her favourite composer was J.S. Bach. I grew up listening to the six Brandenburg Concertos (a Dutch orchestra) and Wanda Landowska’s Goldberg Variations. Bach was God. Of the English my mother would say, “After Henry Purcell there was no English composer of note.”

I finally understood that my mother’s equivocal opinion was based on the fact that there were very few recordings in the 50s of any composer that was not Bach, Mozart or Beethoven. We know better now.

Knowing this did not stop me from uttering to my subject during a photo session, David Lemon, a connoisseur of English music, my mother's thing about after Purcell. He was annoyed. I have come to appreciate Britten, Elgar, Tippett and Vaughan Williams without forgetting my love for Gilbert & Sullivan.

Of Purcell (pronounce with emphasis on first syllable) I will only mention here George Bernard Shaw’s review of a London performance, 21 February 1989, of Purcell’s first (and in English) opera Dido and Aeneas.

Dido and Aneas is 200 years old, and not a bit the worse for wear. I daresay many of the Bowegians [Shaw’s humorous name for the inhabitants of Bow in East London] thought that the unintentional quaintness of the amateurs in the orchestra were Purcellian antiquities. If so, they were never more mistaken in their lives. Henry Purcell was a great composer: a very good composer indeed; and even this little boarding-school opera [composed for a girl’s boarding school] is full of his spirit, his freshness, his dramatic expression, and his unapproached art of setting English speech to music. The Handel Society did not do him full justice: the work in fact is by no means easy; but the choir made up bravely for the distracting dances of the string quartet. Aeneas should not have called Dido Deedo, any more than Juliet should call Romeo Ro-may-oh, or Othello call his wife Days-day-mona. If Purcell chose to pronounce Dido English fashion, it is not for a Bow-Bromley tenor to presume to correct him.

The Great Composers - Reviews and Bombardments

By Bernard Shaw

Edited with an introduction by Louis Crompton.

Walker, Lauren (any youth 18 or under does not pay if accompanied by a paying adult!) and I sat front row centre-left so we could watch violinist Destrubé play a mere five feet away.

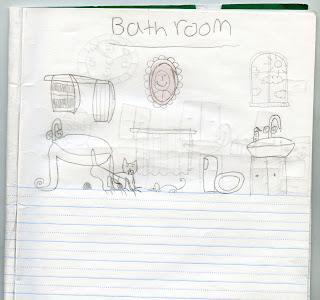

From the beginning I told Lauren that she could sleep, read or draw and that it was a luxury to do any of those things while listening to good music. She chose to sketch. I very quickly became a mano a mano with Walker. The sketchbook changed hands over and over and each drawing has elements of both artists.

One of the two high points for me was to listen to the original piece by Purcell from which Britten wrote his Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, the Rondeau from Incidental Music form Abdelazer. The other was Destrubé’s solo violin performance of Baltzar’s A Prelude for the Violin in G Major. Not coincidentally the piece was composed in 1685 the very date of manufacture of Destrubé’s French violin.

Among my friends of the orchestra, in particular violinist Paul Luchkow, harpsichordist Michael Jarvis and viola da gambist Natalie Mackie there was a new man, Konstantin Bozhinov on Theorbo. Bozhinov, a striking young man from Bulgaria, had my eldest granddaughter have been present, she would have immediately offered him her neck. He was that handsome in that sleep-during-the-day-awake-at-night mode. And he had a fine smile.

I could write about the music, how much fun it was and how fresh it felt but I leave it best to the liner notes written by Destrubé. I have them here as scanned documents. If you click twice on them they will enlarge for better viewing ease.

Note that there will be more Purcell on Sunday March 17 at 4 PM at St. Philip’s Anglican Church, 3737 West 27 Avenue. Marc Destrubé will be accompanied by Arthur Neale on violin, Natalie Mackie on viola da gamba and Valerie Weeks on harpsichord.

|

| Nathan Whittaker, cello |

|

| St. Mark's altar |

|

| Lauren Stewart |