Brother Edwin Reggio, Blaise Pascal & Claire's Knee

Sunday, January 17, 2010

It was two in the morning last night when I found myself not being able to sleep. One word was in my head, Pascal. In the last few days I had seen his name in something and I had been struck by a quote of his. I could not remember. My thoughts went in circles and sleep did not come.

Blaise Pascal argued that if reason cannot be trusted, it is a better "bet" to believe in God than not to do so. He put this forward in his note 233 of his Pensées.

If there is a God, He is infinitely incomprehensible, since, having neither parts nor limits, He has no affinity to us. We are then incapable of knowing either what He is or if He is....

..."God is, or He is not." But to which side shall we incline? Reason can decide nothing here. There is an infinite chaos which separated us. A game is being played at the extremity of this infinite distance where heads or tails will turn up. What will you wager? According to reason, you can do neither the one thing nor the other; according to reason, you can defend neither of the propositions.

Do not, then, reprove for error those who have made a choice; for you know nothing about it. "No, but I blame them for having made, not this choice, but a choice; for again both he who chooses heads and he who chooses tails are equally at fault, they are both in the wrong. The true course is not to wager at all."

Yes; but you must wager. It is not optional. You are embarked. Which will you choose then? Let us see. Since you must choose, let us see which interests you least. You have two things to lose, the true and the good; and two things to stake, your reason and your will, your knowledge and your happiness; and your nature has two things to shun, error and misery. Your reason is no more shocked in choosing one rather than the other, since you must of necessity choose. This is one point settled. But your happiness? Let us weigh the gain and the loss in wagering that God is. Let us estimate these two chances. If you gain, you gain all; if you lose, you lose nothing. Wager, then, without hesitation that He is.

"That is very fine. Yes, I must wager; but I may perhaps wager too much." Let us see. Since there is an equal risk of gain and of loss, if you had only to gain two lives, instead of one, you might still wager. But if there were three lives to gain, you would have to play (since you are under the necessity of playing), and you would be imprudent, when you are forced to play, not to chance your life to gain three at a game where there is an equal risk of loss and gain. But there is an eternity of life and happiness. And this being so, if there were an infinity of chances, of which one only would be for you, you would still be right in wagering one to win two, and you would act stupidly, being obliged to play, by refusing to stake one life against three at a game in which out of an infinity of chances there is one for you, if there were an infinity of an infinitely happy life to gain. But there is here an infinity of an infinitely happy life to gain, a chance of gain against a finite number of chances of loss, and what you stake is finite.

Blaise Pascal, from his Pensées

Brother Edwin Reggio, CSC first told us about Pascal’s wager sometime in 1959 in our religion class at St. Edward’s High School in Austin, Texas. In the context of the times it seemed like a safe bet. I remember that Brother Edwin told us of the wager with a very straight face and did not push us to think about it in one way or another. Since Brother Edwin was a math whiz he explained it all with a wealth of statistics. His dissertation on Pascal was as neutral as his explanation of Aristotle’s’ “unmoved mover” and its re-interpretation by St. Thomas Aquinas. Brother Edwin was not out to proselytize but to simply place the facts as he knew them and from there we could make up our minds for ourselves.

So being awake at two in the morning and with no prospect of sleep I decided to track down the Pascal that was consuming my thoughts to an obsession. I went downstairs and fired up my computer. It opened on my home page, the NY Times. I put in the top left search rectangle, Pascal, and was instantly rewarded with the source which was a lovely paean/memorial to recently deceased French film director Eric Rohmer by André Aciman called My Nights with Eric. I had read it in the Saturday edition of the hard copy version of the Times. If you have access to the online version you can find it here. It is beautiful.

The quote in question was:

With Eric Rohmer, as with Mozart, Austen, James and Proust, we need to remember that art is seldom about life, or not quite about life. Art is about discovery and design and reasoning with chaos. If there is one thing I will miss with Eric Rohmer’s death, it is the clarity, the candor and the pleasure with which one human can sit with another and reason about love and not forget, in Pascal’s words, that “the heart has reasons that reason knows nothing of.”

I must confess that I have never seen one Rohmer film but I have been affected by a still image (I first saw it so many years ago in film reviews) of his film Claire’s Knee. I reproduce it here and hope that nobody will pursue me for using it without permission. The still is one of the most wonderful film stills I have ever seen. I have read reviews of the film and read many articles and essays on Rohmer’s life as a critic, writer and film director. I have now put by reserve dibs on the Vancouver Public Library’s copy (they have two) of Claire’s Knee and I look forward to the discovery of a man that I should have known about years ago.

The Pascal quote in the André Aciman essay made me think (with a smile in my face) that the mathematician and wagerer that Pascal was still had room for such a romantic view on the human heart.

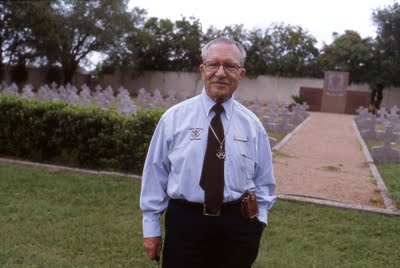

It was last summer that I spent a few days with Brother Edwin Reggio and he invited me to spend some time in hismonastic retreat, which is his place of residence by the old main building that was our school. I had lunch and dinner with him, and his associates, who all seemed to live a life of knowing that whatever wager they had made with life when they were young novitiates was a wager that was well chosen. They were now reaping the benefits of a win. I watched Brother Edwin’s face, full of contentment, his easy demeanor and what seemed to be a complete lack of stress. He smiled in my direction paternally, the once-teacher and now my friend. I almost wish he had been a bit more forward about telling us of Pascal’s wager. Could it be now too late for me to play that game?