The Squirrels Had nothing to be frightened of

Wednesday, October 08, 2008

In 1949 Ilived in the Buenos Aires suburb of Coghlan on Calle Melián which was not far from the Pirovano Hospital. Beautiful black-lacquered hearses, drawn by four shiny black stallions with black plumes on their head, frequently passed by, empty, on their way to the hospital morgue. Because our street, like many then, and even now, were paved with large Paris style cobblestones we could always hear the precise clicking of the horse's hooves. We lingered in the hope of spotting the coffin behind the beveled crystal windows.

Not long after I searched our garden plum trees for the appropriate horqueta or "y joint" that I could cut off to make an honda or slingshot. We always used a discarded bicycle inner tube to make the elastic part of the weapon. I then attempted to shoot any unlucky wren silly enough to rest in one of the plum trees. A few did and eventually I had my first kill. I was appalled and almost ashamed when I saw the dead bird on the grass. It was really my first look at death.

I remember connecting with the character that Molly Parker (as a young girl) plays in the 1999 Lynne Stopkewich film Kissed. In it she buries dead animals from her garden with lots of pomp and ceremony in blue Birks boxes. I never shot at a bird again with that slingshot.

Two years later, in 1951, my cousin Jorge Wenceslao de Irureta Goyena spotted a very large toad in an estancia north of Goya in the Province of Corrientes. He began to hit it with a large stone. I tried to stop him but to no avail. A few days later my uncle Tony (Wency's father) took us into the jungle with his .22 rifle. The jungle canopy was a loud green cloud of thousands of parakeets. We stopped and then Uncle Tony began a systematic execution of the birds telling us they were a plague. After 50 or 60 of them plummeted from the upper branches of the trees we went back to the estancia house.

On July 26, 1952 Eva Perón died. I saw darkish b+w newsreels in the movies of the capilla ardiente a word that means a fired chapel but is simply a hocus pocus name for a place where a body lies in state with lots of candles and military guards. The music was Beethoven, Chopin and Lalo and there were many closeups of grieving descamisados (Peronist shirtless ones as Perón called his followers). Eva Perón was my first taste or awareness of human death. I was 9. Every evening when I was put to bed my mother turned on the radio. It did not matter what station it was as the program was always interrupted at 20:25. "It is 20:26," an Orson Welles voice boomed, "the hour when Eva Perón, the spiritual leader of our nation gained immortality."

In the fall of 1966 my Armenian uncle Leo Mahdjoubian phoned. He didn't pull any punches. He simply told me, "Your father kicked the bucket yesterday and you should know." My father had died (DOA at the Pirovano Hospital) with enough money in his pocket that I was able to pay for a modest funeral. It was the first time in my life (once again for my mother) that I went shopping for a coffin. There was enough money left over to pay for a 7 year residence in Chacarita the large Buenos Aires cemetery where the masses are buried.

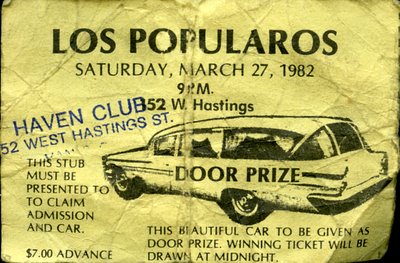

On March 27, 1982 I purchased a ticket (number 175) to go to an underground concert with my favourite alternative band, the Popularos (below, with Art Bergmann middle row, right). It was my lucky night because I won the white Pontiac hearse. The organizers gave me the choice of the car or $500. I took the money. I put $250 in the bank and then bought $250 worth of beer (that was lots back on 1982) and invited all my alternative musician friends to a party. The beer was put into a bath tub. By the end of the night Zippy Pinhead (second row, left) was carried away and I was able to confirm there was still beer left in the tub.

Sometime around 1989 I bought an air gun at Three Vets. It was a beautiful immitation .44 magnum which came with two barrels, a short one and a long one. In 1989 I was an eager but mostly ignorant gardener and I thought our garden squirrels were out to eat all our spring bulbs (I was partly right). I made the decision that I would shoot the varmints (that fine word the Americans like to use). But I decided I was going to give the little animals a spoorting chance by not wearing my glasses. I would quietly but suddenly open the kitchen door and then raise my gun. I would aim and shoot. I managed to get one. I saw it leap up when I shot it and it disappeared in a hosta bed. I went out searching and found the little animal agonizing but still alive. The animal was suddenly that wren from so long ago in my Buenos Aires garden. I gave the squirrel its coup de grâce and retired the gun on a table in the living room. When Hilary (not yet Rebecca or Lauren's mother) found out she told me that if I attempted to shoot any more squirrels she was going to call the SPCA. A few weeks later we had a burglar who stole my stereo, my CDs and the gun. When I made my insurance claim I kept the offending gun from the list.

In 1989 I returned to Argentina for the first time since 1967. I visited my half brother Enrique and my nephews. One in particular, Patricio (affectionately nicknamed Pato or Duck) was especially interested in all things George as they all call my father and their grandfather. Patricio asked me about Chacarita and I told him that George's tomb would not be there anymore as they would have dug it up after 7 years and thrown its contents into a mass grave or filled some hole with its rubble. He looked at me with disgust. I forgot about it. A couple of days later Patricio came up to me and threw a little square marble stone on the table. He almost hit me with it. "I looked at the records to find where George was buried and located a Juana Esmeralda. She took George's place. I found this white pebble. Perhaps it had some contact with his bones."

Death has been in my thoughts of late here here and here. I have been at it for years because of my exposure to philosopher and teacher Ramón Xirau who taught me about Epicurus of Samos in 1964.

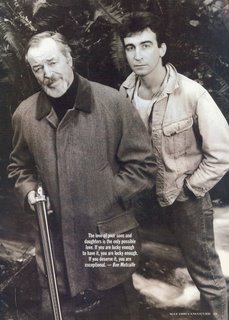

For years I have avoided reading the books of British author Julian Barnes simply because he has a startling resemblance to a friend of mine, Michael Metcalf (seen below to the right of his father Ben) who committed suicide with a drug overdose. But I had to finally rescind my own prohibition and last night I began his latest nothing to be frightened of (Random House Canada 2008). Barnes describes his father's death:

He died a modern death, in hospital, without his family, attended in his final minutes by a nurse, months - indeed, years - after medical science had prolonged his life to a point where the terms on which it was was being offered were unimpressive. My mother had seen him a few days previously, but then suffered an attack of shingles. On that final visit, he had been confused. She had asked him, characteristically, 'Do you know who I am? Because the last time I was here, you didn't know what I was.' My father had replied, just as characteristically,'I think you are my wife.'

In the New York Times review of Barnes's book Garrison Keillor states:

I don't know how this book will do in our hopeful country, with the author's bleak face on the cover, but I will say a prayer for retail success. It is a beautiful and funny book, still booming in my head.

I am happy to report that so far I agree and furthermore I would like to add that the Canadian edition of nothing to be frightened of does not have Julian Barnes's bleak face on the cover.