Flaming Facebook

Tuesday, March 16, 2010

By the end of 1994 my friend Celia Duthie was talking about the World Wide Web and something called wimsey. I had no idea of what she was talking about. She compounded my confusion by telling me about a new powerful Sun Micro System device that was going to make her bookstore an on-line store.

In March of the next year with the help of Duthie I opened an account with a local service provider called wimsey and I was given my first e-mail address

[email protected]. I remember calling the wimsey tech support chap one day and he asked me, “It’s raining here on 4th Avenue. What is it doing by your neck of the woods?” Little did I know that pick-up-the-phone-and-call-for-tech-support would be a thing of the past and soon I would be talking to persons in Rumania who would not help me with my FTP blogging problems. We would be having no-language-in-common problems.

Then I went to Duthie’s with my wife’s IBM laptop (it was called a think pad at the time) and I connected to the internet for the first time. Duthie went to France and I decided to pitch a story to

Equity Magazine about a daily e-mail communication with Duthie in France. The article was published in May 1995 as

(Almost) on-line from France with Celia Duthie: diary of a techno-illiterate's battle to send an electronic letter. The techno-illiterate was, of course, me!

At the time I was barely able to use my computer. My friend Paul Leisz had written me step by step instructions which began, “Turn computer on.”

For close to 6 years I wrote articles for magazines and newspapers by using a Smith Corona Word Processor. I would print out my manuscript and then type into Eudora which was an early equivalent of Microsoft’s Outlook Express. One of the editors I submitted my stuff was Nick Rebalksi at the Vancouver Sun. He never objected to my format method. It was later around 2003 that I finally stopped using the Smith Corona and learned to use Word.

Shortly after getting connected to the internet I joined an Electronic Round Robin of the American Hosta Society. It was a de facto social network many years before the likes of My Space and Facebook. And it was a bit more that the contemporary electronic bulletin boards of the time. Before I joined that electronic round robin I had been a member of the plain round robin. I was part of a group of 6 hosta enthusiasts who would write in a letter and enclose it in a package that included the letters of the five others. Some of us were lazy and sometimes it would take a couple of months for the round robin to makes its rounds. One of the members of the robin was Alex Summers, the founding member of the American Hosta Society. He had wonderful and intelligent things to say but his handwriting was illegible! We were civil and I enjoyed the process.

The electronic round robin was much more direct and there were many more than 6 members in it. It was, looking at it with contemporary hindsight a specialized botanical community out of something like Facebook.

We all had opinions ( Is hosta hyacinthina a species

Hosta hyacinthina or a cultivar

Hosta ‘Hyacinthina’) and we rarely were uncouth. Those who were uncouth were flamed. It was fun and soon I was at it more hours than I should have been. There was one member of the robin (a friend of mine who lived in the US Midwest who decided to play a prank. He stayed up at night and was known to drink heavily. He had mastered the technique of having many email identities. With a couple of them he would write opinions contrary to his own opinions and then fan the flames between his two personalities. Soon our robin was a mess and people were insulting each other. I caught on (it seems that in spite of my low techno-illiteracy I had been able to read the clues). I called him up and he told me he was having a ball.

Soon one of our members, who was a lawyer, had hired another to write up a “constitution” that would regulate behavior in the robin. We were summarily given two days to sign or opt out. Many of us, including me, cited the constitution as being neo-Hitlerian in character and we signed off. My friend, the culprit, signed and remained. I never returned to the robin.

I past years I have been members of photographic forums (these are similar to the American Hosta Society Round Robin) and in no time photographers are insulting each other and moderators intervene and banish the offenders for days or permanently. I quickly lost interest in these forums. A typical photographic forum question might be, “Do you ever get sexually excited when you photograph a nude woman?” or “Which is a better camera a Canon EOS Jaguar Four-Door or a Nikon Lumix V-8?” The perennial, “Which is better digital or film?” garners tons of back and forth insults. If you happen to point out that a posted picture has flaws you are quickly told that your opinion was not asked.

A friend living in Spain wrote to me telling me she wanted me to look at her pictures but that she did not know how to send me jpegs. I was to join Facebook so I could see them. I reluctantly did this under my official first name (in Spanish) and with my mother’s maiden name. I saw her pictures and then became curious about Facebook. After a year of it I have gotten multiple requests from men in Barcelona and in Madrid who want to be my friends. Mexican photographer Pedro Meyer sent me a request for me to be his fan!

Perhaps what I dislike the most about Facebook is the unreal concept that those in a circle or community live in a world where everything is “gosh, that’s lovely!” and people exchange platitudes in increasingly Twitter-like brevity.

I don’t have a Facebook circle since I mostly read what some of those would-be friends write about while I “publish” photos in my wall with comments on them (all in Spanish). A few days ago I saw some photographs of a Spanish model/photographer with whom I e-mail some years ago. She lives in Madrid. These pictures were taken by another photographer. They made the freckled-faced beauty look older, rough and downright unattractive. I wrote a comment (I should have known better) that I longed for her to take more self portraits and that the photographer in question should perhaps switch to another profession. I was immediately lambasted with several comments that I should keep my comments in a positive way and that the photographer in question was really a good guy and was an excellent photographer. I stuck to my guns and wrote another comment (I should have known better!) that there are photographic standards and that at the present rate photography as we know it is drifting into a uniform mediocrity. To make it all worse I quoted my grandmother in Spanish. One quote refers to our Darwinian origins, “He showed his tail.” And the other “Ignorance is daring” is all about the fact that now anybody can “publish” any photograph, anywhere, any time.

This got me into hot water and the photographers around the model’s social circle went after me with a vindictiveness that was scary. I did nothing and called my own retreat.

In a world where we still have tests and grades in schools it is evident to most that there are good students and bad students. We cannot all excel in the same profession. Yet in Facebook all photographs are wonderful, exciting, interesting and nobody calls a spade a spade.

I cannot reconcile the idea that some can and some can’t with the politically correct concept that we all can if we try.

I am giving Facebook a skip. I should have known from my days of the Electronic American Hosta Society Round Robin.

Lillian Gish - First Lady Of The Silent Screen

Monday, March 15, 2010

First Lady of the Silent Screen

By John Lekich

Special to the Globe and Mail

Friday, October 24, 1986

At 90, Lillian Gish can’t seem to shake the habit of talking with her eyes. Some 75 years after making her silent film debut in D.W. Griffith’s

An Unseen Enemy, her eyes can still swell with a purity of emotion beyond speech. As the light from the window of the Meridian Hotel coffee shop sifts across her delicate Victorian features, it’s almost possible to believe that the slightest sound would be a pointless intrusion.

Gish recently attended the closing gala of the Vancouver International Film Festival, where Jeanne Moreau’s

Portrait of Lillian Gish was screened. The woman dubbed “The First Lady of the Silent Screen” not only speaks plainly, but with impeccable diction that befits a former pupil of Toronto’s legendary Mrs. Carrington (the vocal coach who, as John Barrymore once confided to Lillian’s sister Dorothy, “saved me from being nothing more than a fifth-rate actor”).

Among the animated tones, there’s enough honest wisdom to explain the late Griffith’s contention that Lillian Gish “is not only the best actress in her profession, but has the best mind of any woman I have ever met.”

Says Gish: “Oh, I have an awful memory. I could never lie because I would always forget what I said. So I had to tell the truth. And it worked out rather well. Because people tend to respect you if they know you’re just being yourself.”

Despite downplaying her memory, Gish, who once labeled Hollywood “an emotional Detroit,” vividly recalls a vast array of anecdotes that span several eras of show-business history.

A performer since the age of 5, she remembers dancing in a play opposite Sarah Bernhardt (“She was the woman who made it possible for children to work on the stage”), taking her first curtain call on the shoulders of Walter Huston (“I was so scared that I tried to run downstairs and hide behind some boxes”) and portraying Alan Alda’s “slightly off-centre” mother in his recent

Sweet Liberty ( “I turned down the part five times because I thought he looked much too young to be any son of mine. But after a few minutes of looking into that beautiful face, I thought: ‘I’d work for this man for nothing’”).

“I never chose money,” she says. “I always chose people. I wanted to be around people who knew more than I did. I think that’s why I never fell in love with an actor. They never seemed to know any more than I did. I wanted to be with writers…My idea of a dream man was Thornton Wilder.”

Describing herself as “endlessly curious,” she’s resisted matrimony (“I’ve always love men. But I would never ruing their lives by marrying one”), traveled extensively (“I’ve been everywhere except China because I know I’d end up walking too much for my own good”) and sampled life on the other side of the camera (“In 1920I directed Dorothy in a film called

Remodeling Her Husband. That’s when I discovered that directors don’t sleep well at night”).

Yet, curiosity had little to do with the Gish sisters’ initial involvement in silent pictures. Born a year apart, the girls had more pragmatic reasons for working in movies.

“We were hungry many times,” Gish says of a childhood that included a wandering father who refused to support the family and a struggling mother who “was as near to God as I would ever get.”

“The only place that would have us was the movies,” she adds. “And in those days, that was really scraping the bottom of the barrel. Our biggest fear was that someone from our home town in Ohio would see our name in the paper. In the Midwest, a proper girl got her name in the paper three times. When she was born, when she got married and when she died. Otherwise you were a loose woman.”

In 1912, neither Lillian nor Dorothy realized that, by simply entering the offices of Manhattan’s American Biograph Company after seeing neighborhood friend Mary Pickford in the movies, they’d end up changing the face of the silent screen.

In a time of crude photography, “where you were a character actor by the time you were 8,” Griffith put the two teenaged sisters to work immediately. Tying different colored ribbons in their hair so he could tell them apart (“He would shout: ‘Blue over here! Red over there!’) they began a relationship that would see Dorothy grow into a skilled comedienne, while Lillian became the era’s foremost dramatic actress through such Griffith classics as

Broken Blossoms,

Orphans of the Storm and his 12-reel epic,

Birth of a Nation.

Gish has high praise for Griffith, the man credited with virtually inventing the language of filmmaking. Recalling his pioneering use of the close-up, she says: “The people in the front office got very upset. They came down and said: “The public doesn’t pay for the head or the arms or the shoulders of the actor. They want the whole body. Let’s give them their money’s worth.’

“Griffith stood very close to them and said: ‘Can you see my feet?’ When they said no, he replied: ‘That’s what I’m doing. I am using what the eyes can see.’ ”

Gish also helps to explain why his improvisational methods proved impractical with the advent of sound.

“The only writing you saw on a Griffith picture was his signature on your cheque each week, “she says. “There was never any script. You never knew what the plot was in advance. He would stand at the back of the room and call out the story as you walked through it a couple of times. Finally, freely and without thinking, you said whatever lines you felt the character might say in that situation. That was the direction. That was the way I worked for nine years.”

The same creative faith often overlapped into instances where she would risk life and limb. Nowhere is this more evident that in the 1920’s

Way Down East. In one of the screen’s most unforgettable moments, the climax finds Gish lying on a huge ice floe, her long, flowing hair and the fingers of on hand trailing across the frigid water as she heads for the falls.

Holding up her right hand she exhibits a couple of bent fingers. “It was my idea to put my hand and hair in the water, she says. “The water was so cold that it burned. I had no idea it was going to hurt so much. Of course, you can’t blame anybody but me for that.”

She has steadfastly refused to use a double throughout her career. “I’ve always felt you could tell the difference,” Gish says. “People move differently…Of course, in those days, everybody fell off everything. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been thrown off a horse.”

Working well before the development of unions also meant putting in 12 hours a day with not time for anything else but sleep. While she once worked 25 hours at a stretch before her bloodshot eyes prompted a disgruntled cinematographer to send her home for a restorative nap, the actress looks upon those early days with Griffith as among the best in her life.

“We were like a family,” she recalls, painting a picture far different from the Fatty Arbuckle and William Desmond Taylor sex scandals that would later rock the infant industry. “With Griffith there were definite rules. We weren’t allowed to kiss anybody. If a scene called for it, you’d put your lips near the leading man and the camera made it look like they were touching. But we never actually did it.”

She remembers when the theatrically trained John Emerson was lent to the studio to direct the 16-year-old Dorothy in 1914’s

Old Heidelberg. “They came to a scene where John said, ‘All right Dorothy, now you kiss so and so.’ Dorothy just looked at him and said: ‘Oh we don’t do that sort of thing in this studio!’ ’’

The issue of to kiss or not to kiss split the company in half, but “pretty soon,” Gish says, “The actor’s wife called our mother and explained that it was quite all right for Dorothy to kiss her husband. He had no diseases and it wouldn’t hurt her. So Dorothy had to do it. But, since neither of us had ever been kissed, she didn’t exactly relish the idea.”

In 1913, Gish migrated to Hollywood in search of weather that would allow Griffith’s company to use sunlight all year long.

“There was no Hollywood then,” she says. Griffith invented it. We worked out of a little shack on the outskirts of L.A. where the city used to store their streetcars. But I thought we’d found paradise. It was orange blossom time and the mockingbirds would sing you to sleep every night. It was so beautiful.”

But she would never forget Griffith warning her about the very thing he had helped to create. “He said, ‘Don’t let this place fool you. It’s very good for your body and very bad for your mind and soul.’ Of course, he was right, but somehow I managed to survive.”

Not that surviving Hollywood was easy. By mutual consent, she reluctantly left Griffith for a higher salary and greater creative control – eventually joining MGM in 1925. Stepping off the train from New York, she began a lifelong friendship with Irving Thalberg, the studio’s wonder boy, by mistaking him for the baggage clerk.

“He looked all of 18 years old,” Gish says of the man F. Scot Fitzgerald would later use as the model for

The Last Tycoon. “He was a wonderful, brilliant man – consistently amused by the fact that people were always taking him for the office boy.”

Her relationship with Louis B. Mayer was far less pleasant. She credits Mayer- the only person she expresses even the vaguest dislike for – with putting a virtual halt to her film career throughout the thirties.

“He always insisted that any film with an unhappy ending would ruin your career,” says Gish, whose handpicked projects with MGM included King Vidor’s

La Bohème and Victor Sjostrom’s

Scarlet Letter. “L had seven unhappy endings.”

While such films proved successful, they worried the commercially conscious Mayer. “He called me into his office one day and said” ‘You’re sitting way up there in a pedestal and nobody cares. Let me knock you off and everybody will care.’

“He wanted to stimulate box office by creating a scandal for me the way he did for John Gilbert and Greta Garbo,” Gish says. “He said that they had Garbo now and they really didn’t need me. So if I refused to play along, he’d make sure I never got another job in the movies.

“I thought to myself: ‘I’m going to have to give a performance on screen and off screen if I am going to be a sex symbol. I went back and told him: ‘I’m sorry Mr. Mayer. But I don’t have that much energy.’ ”

Finding jobs scarce in Hollywood she returned to the stage, where Jed Harris offered her the role of Sonya in the U.S. premiere of Chekov’s

Uncle Vanya (“Harris was like Griffith,” Gish says. “A genius. I got along well with genius.”) Subsequent roles included Ophelia opposite John Gilgud in a legendary performance of

Hamlet (“Gilgud didn’t play Hamlet, “Gish says. “He was Hamlet”), and an 18-month run in

Life With Father (“I spent a year and a half running upstairs. That’s a lot of exercise when you include matinees).

“I found that I truly loved the theatre,” she says, adding that her only regret was that a play prevented her from attending Griffith’s funeral in 1948. “But the best part of being on the stage was that I didn’t have to go back to that mean Mr. Mayer after he tried to ruin my career.”

Through it all her stipulation for accepting work has been the thought of trying something different with people she admires. (She accepted her role in Robert Altman’s

A Wedding because “he said you die, but you die with comedy, I like that.”)

Gish characteristically refused to say anything negative about the current state of the movies. “I don’t see enough films to make a judgment,” she says, “although I laughed until I cried at

Tootsie. And

Gandhi was four hours that seemed to go by in four minutes.”

Still, she admits to missing silent films, and tours with her favorite, 1928’s Wind, every chance she gets. “At that time,” Gish says, “only about 5 per cent of the world could speak English. Silent pictures not only changed the world, they controlled it. Then with a smile that makes you wonder why they ever bothered to make talkies in the first place she adds: “Who knows? Maybe some day they’ll come back.”

Re-published by kind permission of the author.

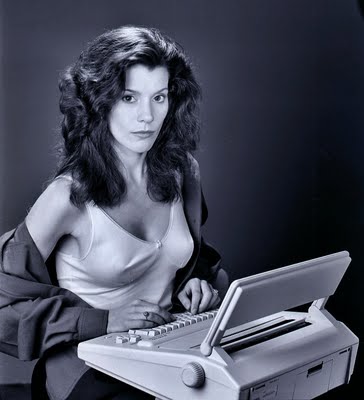

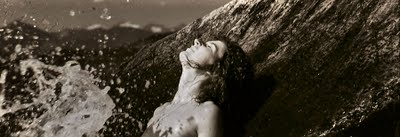

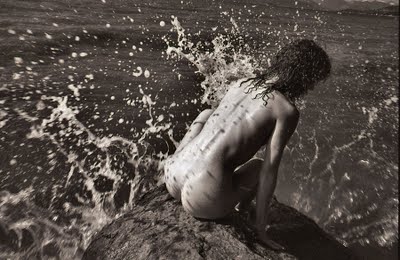

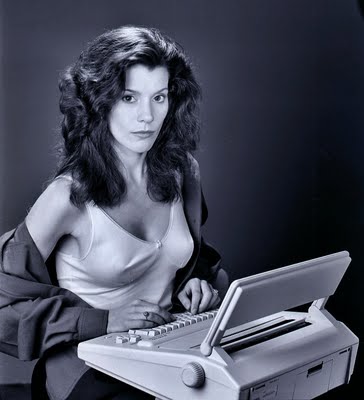

The portraits here are not of Lillian Gish but of my granddaughter Rebecca Stewart who rose to the occasion when I suggested the project to her.

Alex Waterhouse-Hayward

From The Heart

Thursday, March 11, 2010

From the moment that I can remember being an individual I can remember my mother opening a heavy but small jewel box and showing me the heart of diamonds. Of all the jewels (purchased in Paris) that my grandfather Tirso de Irureta Goyena had showered on his bride and wife my grandmother Dolores Reyes de Irureta Goyena the only one that was left was the little quartz heart studded with diamonds. The rest of the jewels had been pawned off or sold to finance the divorces of my uncles and aunt.

When Alexandra Elizabeth (our first daughter was born in 1968) my mother told me that it was her will that the heart would be used to finance Alexandra’s university education. “I want her to have all the opportunities she deserves,” she told me.

Both Ale and Hilary managed to graduate from university here in Vancouver. Ale went to UBC and Hilary to Simon Fraser. What is to happen to that little heart of diamonds? I would think that my mother’s will, would transfer to our eldest granddaughter. We shall see and keep the little heart in its box.

Fulfilling the wills and desires of someone who is dead is something that most of us take most seriously.

I never thought that I would have to do this for someone else.

It was this past July that my friend Abraham Rogatnick shocked me with a statement that I first took lightly. He said, “

If there is anything I want to do before I die is to go public on my stance that the Vancouver Art Gallery should stay put.” He wrote up his reasons and went to visit Vision Councellor Heather Deal. Deal read the “manifesto” and said something like, “

Let’s wait and see.” Rogatnick told me, “

I lost it and I yelled at her, what do you mean you are going to wait and see?”

I told Rogatnick to give me his manifesto and that I would try to see if anybody was interested. By mid August Rogatnick was ailing and I told him I had been unsuccessful in my efforts to get the radio, TV, web based magazines and our local newspapers interested. Rogatnick simply told me, “

You tried.”

This past Monday I can say now that thanks to the intersession of the Vancouver Sun’s city columnist, Miro Cernetig, Rogatnick’s manifesto is up in today’s Vancouver Sun editorial page.

Rogatnick did not believe he was going anywhere when he died at the end of August of last year. I felt I had let the man down.

But Rogatnick was always pragmatic and he would probably agree with me that his

manifesto might be that much more effective coming from the grave than when he was alive. My thanks to Miro Cernetig for keeping Rogatnick’s vision alive.