Guest Blog

NAS Whidbey Airshow … Rossiter… 15 August 94

Former Navy pilot Stephen Coonts is working on a follow-up to his novel Flight of the Intruder, from which Paramount Pictures derived the popular Vietnam action movie in which a Navy A-6 crew decide to buck the president’s bombing guidelines and attack Hanoi. Coonts’s novel contains some of the best evocations of military flying since Pierre Closterman’s WWII memoir The Big Show appeared in 1951. Both books remove the romantic veneer from the war in the air, at least partly because bombing is so much more dangerous and morally ambiguous than air-to-air combat.

The movie was distributed to carrier air groups during the Gulf War, when it might have been expected to boost morale. It was, after all, the first depiction of the nerd of carrier aviation, Grumman’s A-6 Intruder. To real-life A-6 flight and ground crews, though, the flyboy caricatures they saw of themselves were a grave slight. Like most aviation pictures, Flight of the Intruder is in trouble as soon as the action returns to the carrier deck.

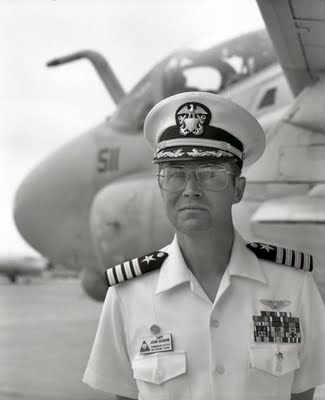

Maybe Paramount will do better with Coonts’s new book The Intruders. The actual A-6 community is more complex is infinitely more interesting than director John Milius’ portrayal. Certainly more professional. Capt. John Schork’s bomber-pilot war stories are less about combat than accounts of the ongoing battle with fear of celebrations of sheer technique. Peace stories you might call them.

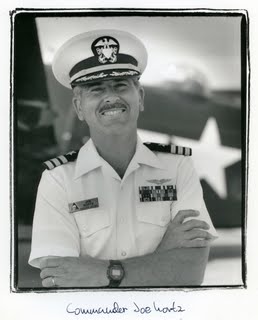

The Naval Air Station Whidbey Island’s executive officer, Commander Joe Nortz (think of the Tom Skerritt character in Top Gun but with fewer wrinkles), had promised us war stories. Not only would we hear war stories, but the guy telling them would be the base commander. NAS Whidbey’s CO, Schork flies more than a desk. He has flown the A-6 Intruder in three wartime situations, and he keeps himself current.

He told his first story with an arresting special effect: flames reflected in the left sides of his GI sunglasses. The explosives set off to simulate the effects of a pop-u bombing run by an A-6 had ignited the tinder-dry grass across from the air show flight line at NAS Whidbey’s annual Sea-N-Sky Festival last July. It was burning out of control.

The fireman supporting the A-6’s air show demonstration of bomb delivery techniques had put on a more impressive display than anybody had intended. Every once in a while a staff officer in immaculately-pressed dress whites would appear out of nowhere to whisper a firefighter’s progress report into Schork’s ear while he coolly offered his interviewer vivid reminiscences of two decades in the cockpit of the Navy’s deadliest combat airplane.

“The thing that really sticks with you is, we go out and fly low-level, high speed terrain-following through these mountains”- Schork makes an almost imperceptible motion with his right hand, past the fire raging 200 yards away, to the Cascade Mountains ---“and no matter how long you fly the airplane, you never lose the thrill….

“The only thing between me and the rocks and trees is good electronics and training. Every time I do it – and I’ve been doing it for 20 years – it is a thrill. There are few jobs,” he adds, quite unnecessarily, “where you get that kind of exhilarating feeling.”

Schork grew up in nearby Oak Harbor and is still among the most proficient A-6 drivers at the base. The Thursday before we met his name was spelled out on the base’s E for Excellence scoreboard as the current winner of the Norden Picklebarrel Award as the most accurate bomber pilot in attack squadron VA-128, NAS Whidbey’s training unit. (Norden is a maker of bombsights; a pickle barrel is what a good bomb sight enables you put your bombs into.) “I’m a little embarrassed, “Schork said, sounding pleased as punch. “The trophy is for the young guys, not old-timers like me.” Not only Schork was the most accurate pilot in its Replacement Air Group, Attack Squadron 128, But NAS Whidbey, his command, was the best installation in the Navy worldwide. He was having the month of his life.

Schork is a compact, thoughtful and intelligent man with a self-deprecating sense of humor who calls himself the worst quarterback in the history of Oak Harbor High. He has none of the professional warrior’s mannerisms. Maryanne Kilkenny, wife of VA-196’s executive officer, who returned from a six-month cruise aboard the carrier Carl Vinson last Sunday, calls Schork “a wonderful man,” an uncommon encomium in the military. (VA-196 “Main Battery,” by the way, is the outfit portrayed in Flight of the Intruder.) In every way except bulk he personifies the airplane. The two, man and airplane, have matured together since he first flew the A-6 in combat over Saigon the day the city was being abandoned to the North Vietnamese.

This year’s Sea-N-Sky Festival had an almost nostalgic undertone to it. NAS Whidbey exists as the largest naval air station on the Pacific coast – 9,000 on active duty and 2,500 civilians – because of the Grumman A-6 and EA-6b Prowler, its electronic warfare derivative. Working together with the lengthened, crew-of-four, EA-6B jamming enemy anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) and SAM radar, and the two-seat (pilot, bombardier-navigator) A-6 dropping bombs, the Intruder-Prowler team are the fleet’s sharp point. There is also a tanker version, the KA-6D. Several of NAS Whidbey’s squadron carry battle honors from the Gulf War and subsequent enforcement of the no –fly zone over Northern Iraq.

But there is no room in the Navy budget for further development of the Intruder/Prowler design. Thirty-four years after it first flew and a little more than three decades since it entered service, the A-6 is facing retirement. Three generations of naval aviators devoted their careers to it. Throughout its service life, they have celebrated it by pointing out that no other carrier-based combat aircraft could, as they put it, reach out and touch someone – anytime, anywhere. VA-196 is scheduled to be the last A-6 squadron in the Navy. It will be decommissioned in 1996.

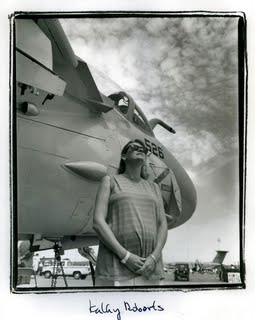

Whidbey, identified as “Intruder Country” on one of its cavernous hangars, where the shriek of A-6s is thought of as “The Sound of Freedom,” wonders what could possibly replace the A-6. “It’s not so much the airplanes themselves,” says blonde and pregnant Kathy Roberts, even though her husband “loves it” and carries a picture of one in his wallet. “Does he carry a picture of you?” she is asked. “I don’t know!” she exclaims. “It’s not the airplane,” she says, “It’s the mission. It’s the whole responsibility of what he does.”

When it first flew in 1960, the A-6 was the smartest airplane in the fleet. An expensive airplane to begin with, 43 percent of the $25 million-a-copy (1990 dollars) Intruder’s cost was accounted for by its electronic equipment – an unheard-of proportion of brains to brawn. It had an onboard computer driving cathode-ray tube (CRT) displays for both pilot and bombardier-navigator, a feature introduced to commercial aviation on Boeing 757-767 airliners 15 years later.

Although the first four A-6 Intruders lost in combat over Vietnam were listed as having been downed by anti-aircraft artillery, aviation historians believe three of them were more likely to have been destroyed by their own bombs. The price of pioneering in warfare is usually high, and it was at least mitigated by excellent British Martin-Baker ejection seats that saved the lives of all eight crewmen, two of whom became prisoners of war.

One solution was to use explosives to actually blow the bombs off their racks under the wings. Another was to “pop-up” from the low-level run, climb to 2,000 feet, visually acquire the target by rolling the A-6 inverted, and then aim it at the target. A variation is to release the bombs while climbing vertically over the target. Doing a pop-up imposes a four-G load on the airplane and its crew, whose heads, burdened with helmets and breathing gear, become four times their normal weight. Then again, as the Sea-N-Sky Festival air show commentator, a Confederate Air Force Colonel from Arlington, Texas, explained over the PA, when you bomb while flying straight up, “You can be at home sipping a cold beer by the time the bombs go off.” The pop-up bomb run resolved the suicidal aspects of low-level bombing, which had become necessary because North Vietnam’s sophisticated SAM defenses made conventional high-level bombing out of the question. The technique also happened to create a sensational air show routine, “It looks pretty good from the inside, too,” Schork mentions.

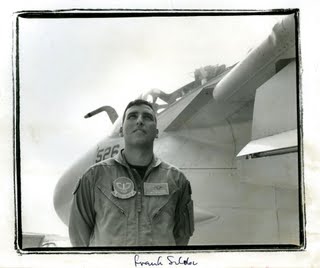

There was an A-6 parked in front of Whidbey’s operations centre during the air show. Frank Silebi was putting in a long hot day in his polished black boots and khaki flying suit by the Intruder’s nose, telling anyone who would listen that he is part of a naval aviation milestone: “the last class ever for the A-6, “three pilots, one bombardier-navigator, doomed to become carrier qualified anachronisms. Silebi was born in Barranquilla, Colombia, but grew up from an early age in Pennsylvania. He can speak fluent Spanish. When Silebi was in flight t training, flying TA-4J Scooter on and off carriers, the withdrawal date for the A-6 was 1999. By the time he had his naval gold wings, the date had been moved ahead by two years. Flying the A-6 is Silebi’s reason for being in the Navy, and for a while he was afraid he might not be trained soon enough to do it. After all he says, “What’s better than flying low and flying fast?”

John Schork (43) and the airplane (34) came up together. Their careers are as one. Smart airplane, bright officer. The current Norden Picklebarrel Tropy holder put in three of his four combat tours with VA-95, the Green Lizards, celebrating 50 years of service last October. Schork’s Green Lizard tours have included his top-cover assignment over Saigon. It is now almost 20 years since John Schork made his combat debut ushering in peace over Vietnam in early 1975. The fire of his sunglass lenses lit up to the story as he described his first taste of the Real Thing, the thing he still wins awards training for: “I can remember orbiting Saigon. I could see Tan Son Hhut airbase burning. I can remember the tracer fire coming up against the gathering dusk, and the smoke, and thinking this was a historic evening. We were flying A-6s, loaded with bombs, as cover. Our helos (CH-53 helicopters) were circulating, evacuating people….” In other words, the A-6 was used over Saigon in a fighter’s role, able to fly safely in darkness. The concern was that if any helicopters were shot down that day, the vengeance impulse might extend the war. None were.

“It was a dependable airplane,” Schork says, lapsing into an early obituary for the A-6. “I’ve seen this thing come back with one of the horizontal stabilizers gone. It’s a forgiving airplane. It’s practically impossible to spin the airplane. I can take off at Whidbey and on-leg-it to Washington, DC. I have flown the thing trans-Pacific. We flew a strike from the carrier in mid-Pacific and flew 1500 miles to the Hawaiian Islands, at night, and flew back to the ship. That’s when you realize how big the Pacific is. Each of us had our own tanker. That’s you’re you realize what the airplane can do. “

There are plenty of guys at Naval Air Station Whidbey Island who feel the loss of their airplane will leave the world a less safe place. They don’t come out and say so. That would be unprofessional. Their wives are more straightforward on the subject.

I remember exactly when I fell in love with the A-6 myself. To me the Intruder and its genius brother, the Prowler, consisted of bulbous noses, bug-eyed and strong but sagging bellies: they were flying dump trucks, worthy of respect but hardly killer sex objects. Infatuation has a lot less to do with looks that with timing and circumstances.

It happened four years ago last Saturday. The air show in Abbotsford, British Columbia was over. The star was a MIg-31 Mach 2-plus turbojet dragster, seldom seen in the West until then. It had drawn audible gasps in the finale by flying low directly at the crowds, pulling up, lighting both afterburners, and climbing on twin sheets of flame, scorching the infield. A Mig-31 is fast but cannot turn, and the Mig Bureau’s celebrated chief test pilot, Valeri Menitsky, had wrung everything the big fighter had to give. The Cold War was already history in 1990, although the hour or so I had spent with the genial Menitski, conversing through a dour-faced interpreter, still felt like a handshake over a vast ideological gulf. After getting to know him beforehand, exchanging gifts, watching him muscle his fighter into turns that took him from the Fraser Valley out over the San Juan Islands and return from his routine soaked with sweat, it came as a distinct surprise to me that the A-6 is the mental snapshot I retain from that air show.

Perhaps the guys from NAS Whidbey felt a reply was in order. As we were packing our cameras and empty sandwich wrappers, a hard-edged rolling thunder directed our attention to our left. The A-6 in mottled grey war paint was maybe 30 feet off the runway and going to beat hell. Its wing appeared to be exactly at eye level, with its external tanks hung underneath in shadow, tangential to its potbelly. The red anti-collision strobe was blinking away underneath the cockpit. It was flying fast enough to generate white condensation in a vortex off its upper wing roots, an effect heightened by its unique tadpole shape and wide two-man canopy with its art deco windshield frame.

In front of the canopy, the Intruder’s in-flight refueling probe stood up and pointed forward like some trans-sonic insect’s feeler. Nose down, tail up, all business, it looked lethal in a way it never did standing on its landing gear on the flight line. The bombardier-navigator saluted as it passed. The A-6 became a blur in front of our turning heads, pulled up, and in an instant was a T-shaped dot dematerializing through the cirrus.

In front of the canopy, the Intruder’s in-flight refueling probe stood up and pointed forward like some trans-sonic insect’s feeler. Nose down, tail up, all business, it looked lethal in a way it never did standing on its landing gear on the flight line. The bombardier-navigator saluted as it passed. The A-6 became a blur in front of our turning heads, pulled up, and in an instant was a T-shaped dot dematerializing through the cirrus.Sean Rossiter is the author of The Immortal Beaver - The World's Greatest Bush Plane, The Otter & Twin Otter and The Chosen Ones - Canada's Test Pilots in Action

Sean Rossiter

Captain John Schork the Novelist