January 27, 1995

Alex Waterhouse-Hayward

5909 Athlone Street

Vancouver BC V6M 3ª3

Dear Mr. Waterhouse-Price [sic],

Thank you for your letter of December 14, which reached me today via Simon & Schuster. I apologize for the delay, but sometimes they take a while.

When I looked at the photos I realized you have a rare gift. You are one hell of [frequently used by this author in his novels with the spelling helluva] a photographer. And you are on a good story, which is much bigger than the demise of the A-6. The aftershocks of the collapse of communism will affect many lives, not the least of which are those people who have made a career of the military. They are the most directly affected, but the devastation is just as total on the families of the engineers and technicians of the so-called military-industrial establishment who are also facing career death.

I would like to tell you this is something new, a phenomenon cause by the fundamental changes in the international scene that make the worlds a safer place for free people, but alas, that is not the case. This is the same process that occurred after the American Civil War, World War I, World War II and Vietnam. Downsizing. Institutional stagnation. Until the next crisis comes along--and it will, it always does—we don’t need or want you folks, nor can we afford you, so good-bye and have a nice life. But leave your name and telephone number just in case, okay? Now back to the problem of the welfare mothers.

Sincerely,

Stephen Coonts

Back in 1984 I had read a new techno thriller called Hunt for Red October by Tom Clancy. There was another novel (far more satisfying for me) also by Tom Clancy, and co-written with Larry bond, published in 1986, Red Storm Rising in which petroleum shortages usher in a scary and most believable WW III.

But it was Stephen Coonts' 1986 novel, The Flight of the Intruder, published, like Hunt for Red October (then considered quite odd) by the Naval Institute which I consumed in one night's reading. Its description on what must be the single most difficult job in the world, to land a jet aircraft on the pitching deck of an aircraft carrier at night, left me amazed. Coonts’(himself a former naval pilot) explanation on the workings of the pilot and his tandem seated BN (bomber/navigator) in the Grumman A-6 Intruder left me with extreme airsickness as I understood that the BN spent most of the time looking down on a radar screen and instruments. If I were to do that in a placid flight on a Boeing 737 I would be sick on the spot! Coonts' descriptions of A-6 Intruder night flights over flack and SAM infested North Vietnam was as realistic as the claustrophobia inducing The Boat by Lothar-Gúnther Buchheim, the cold and misery of Alistair MacLean's H.M.S. Ulysses and Nicolas Monsarrat's The Cruel Sea. The fear in the throat of Coonts' hero Grafton was as real and horrific as the fear and gore of Len Deighton's Bomber.

Since I am now a Canadian citizen I have like most Canadians not been a war mongerer or an enthusiast of war. But it is difficult to deny a childhood of playing with swords, cap gun replicas of Western .45s and waging war with toy soldiers on my mother’s lawn. It is difficult to deny the pleasure and awe with which I enjoyed in the 50s my uncle, Luis Miranda’s collection of war-time Life Magazine. I saw the picture of McArthur returning to Leyte there and ads for Buicks that proudly stated that Sherman tanks had Dynaflow automatic transmissions! It is difficult to deny the influence of four years of high school in Austin, Texas and of many trips to the nearby Bergstrom USAF. It was there that I first saw the towering Boeing B-52 and passed my hands on the sharp edged wing of a Lockheed F-104 Starfighter.

In the mid 60s while in the Argentine Navy I translated into Spanish the operation and maintenance manuals for the then recently purchased Douglas A-4 Skyhawks. I became intimate with these beautiful (for beautiful they are) airplanes and when the Falklands War happened I was more concerned on the loss of what I considered my airplanes than the death of the Argentine pilots who did well enough and died in equipment that had been obsolete back in my days at the navy.

It was difficult to reconcile and understand that my classmates at St. Ed’s in Austin, Texas, as Americans had been part of the Vietnam War that I remember as body count accounts on my weekly readings of Time Magazine. My room buddy John Arnold had been a US Marine who dangled from helicopter cables to save downed flyers in Vietnam. Others from my class died in Vietnam conflicts. My friend grade 9 friend John Straney with whom I had shared my interest in WW II German airplanes and tanks was in the US Air Force in 1967. Of late these classmates have put a face on the body counts and I feel conflicted particularly when I re-read (as I did last week) Coonts’ Flight of the Intruder and its 1994 sequel The Intruders. I cannot so easily dismiss the conservative beliefs of my Texan classmates who own many guns, target practice at least once a week and tell me of their exploits in 'Nam. Who am I to argue after two years of a desk job as a conscript in the Argentine Navy!

Steam catapults make modern Aircraft Carriers possible. Invented by the British during World War II, catapults freed designers from the necessity of building naval aircraft that could rise from the deck under their own power after a run of only three hundred feet. So wings could shrink and be swept as the physics of high speed aerodynamics required, jet engines that were most efficient at high speeds could be installed, and airframes could be designed that would go supersonic of lift tremendous quantities of fuel and weapons. A luxury for most of the carrier planes of World War II, the catapult now was now and absolute requirement.

The only part of the catapult that can be seen on the flight deck is the shuttle to which aircraft are attached. This shuttle sticks up from a slot in the deck that runs the length of the catapult. The catapult itself lies under the slot and consists of two tubes eighteen-inches in diameter arranged side by side like the barrels of a double-barreled shotgun. Inside each tube – or barrel - is a piston. There is a gap at the top of each barrel through which a steel lattice mates the two pistons together, and to which the shuttle on deck attaches.

The pistons are hauled aft mechanically into battery by a little cart called a “grab”. Once the pistons are in battery, the aircraft is attached to the shuttle, either by a linkage on the nose gear of the aircraft in the case of the A-6 and A-7, or by a bridle of steel cable in the case of the F-4 and RA-5. Then the slack in the bridle or nose-tow linkage is taken out by pushing the pistons forward hydraulically – this movement is called “taking tension.”

Once the catapult is tensioned and the aircraft is at full power with its wheel brakes off, the firing circuit is enabled when the operator pushes the “final ready” button.

Firing the catapult is then accomplished by opening the launch valves, one behind each tube, simultaneously, which allows superheated steam to enter the barrels behind the pistons.

The amount of acceleration given to each aircraft must be varied depending on the type of aircraft being launched, its weight, the amount of wind over the deck, and the outside air temperature. This is accomplished by one of two methods. Either the steam pressure is kept constant and the speed of opening of the launch valves is varied, or the launch valves are always opened at the same rate and the pressure of the steam in the accumulators is varied. Aboard Columbia, the steam pressure was varied and the launch valves were opened at constant rate.

Although the launch valves open quickly, they don’t open instantaneously. Consequently steam pressure rising on the back of pistons must be resisted until it has built up sufficient pressure to move the pistons forward faster than the aircraft could accelerate on its own. This resistance is provided by a shear bolt installed in the nose gear of the aircraft to be launched, to which a steel hold-back bar is attached. One end of the bar fits into a slot in the deck. The bolt used in the A-6 was designed to break cleanly in half under a load of 48,000 pounds, only then allowing the pistons in the catapult, and the aircraft, to begin forward motion.

The superheated steam expanding behind the pistons drove the length of the 258-foot catapults of the Columbia in about 2.5 seconds. Now up to flying speed, the aircraft left the deck behind and ran out into the air sixty feet above the ocean. When it then had to be rotated to the proper angle of attack to fly – in the A-6, about eight degrees nose-up.

Meanwhile, the pistons, at terminal velocity and quickly running out of barrels, had to be stopped. This was accomplished by means of water brakes, tubes welded onto the end of each of the catapult barrels and filled with water. The pistons each carried a tapered spear in front of them, and as the pistons reached the water brakes the spears penetrated the open ends, forcing water out around the spears. Water is incompressible, water got smaller and smaller, yet as the spears were inserted the escape openings for the water got smaller and smaller. Consequently the deeper the spears penetrated the higher the resistance to further entry. The brakes were so efficient that the pistons were brought to a complet stop after a full-power shot in only nine feet of travel.

The sexual symbolism of the tapered spears and the water-filled brakes always impressed aviators – they were young, lonely and horny – but the sound a cat made slamming into the brakes was visceral. The stupendous thud rattled compartments within a hundred feet of the brakes and could be felt throughout the ship.

Tonight as he sat in the cockpit of an A-6 tanker waiting for the cat crew to retract the shuttle, Jake Grafton ran through all the things that could go wrong with the cat.

The Intruders, Stephen Coonts, 1994

And in a later chapter that sheer bolt does break off prematurely which leads to some of the most exciting writing account on how Grafton is able to stop his plane before it rolls:

Sliding, turning left and still sliding forward…he felt the left wheel slam in the deck-edge combing, then the nose, now the tail spun toward the bow, the whole plane sliding…

And he stopped.

Out the right he could see nothing, just blackness. The right wheel must be almost at the very edge of the flight deck.

He took a deep breath and exhaled explosively.

His left hand was holding the alternate ejection handle between his legs. He couldn’t remember reaching for it, but obviously he had. He gingerly released his grip.

The Intruders, Stephen Coonts, 1994

My fascination with The Flight of the Intruder led me to go to several air shows at the Whidbey Island Naval Air Station near Oak Harbor in Washington State. I went with my friend Sean Rossiter who like me is an airplane enthusiast. At Whidbey Island I thrilled at watching A-6 Intruders fly. And it was in July 1994, my last visit that I found out that the A-6s where being phased out and replaced by F/A-18 Hornet. I talked to pilots who told me that the thrill (and fear!) of piloting an A-6, very low (skimming the trees) at night and in bad weather could never ever be replicated by the Hornet. In fact to this day the Hornet can not match the Intruder’s range and payload. During its existence as an attack plane (A-6s were never used as fighters but to bomb, strafe military installations and ships) the Intruder could carry a bomb payload that was second only to that of the Boeing B-52.

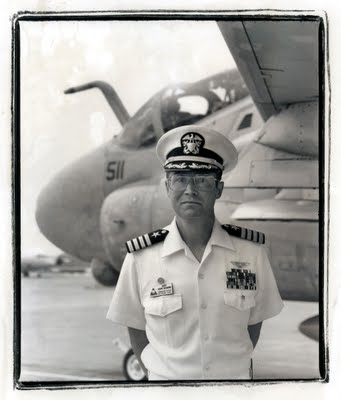

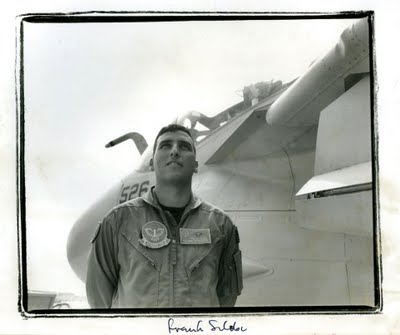

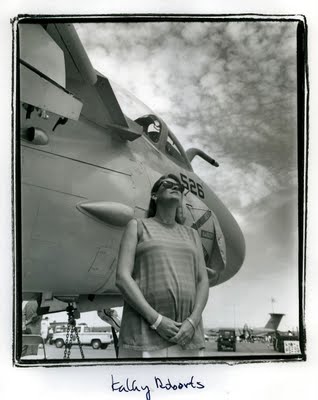

My excitement at seeing the Intruders and taking photographs of the then base commander (who had flown Intruders) Captain, USN John Schork led me to propose to Rossiter that we collaborate on a story and to try to sell it to magazine. We never found anybody interested even though Coonts in his letter to me suggested a few venues. The story died even though Rossiter wrote it. In my files today I found two versions of Rossiter's 6 page story. I called him up for permission to run it. Permission has been granted (story will follow sometime today). Since 15 August 94 when Rossiter wrote his second draft he lost all records of it. The publishing of the story in the blog will be a pleasant and now anticipated surprise for him.

When I re read The Flight of the Intruder (all about Vietnam) and then its sequel The Intruders (no war) I was able to read the technical stuff with far more enjoyment. My ignorance of naval aviation is perhaps the only reason why in my Buenos Aires war games I was never a naval pilot!

The splotches of the pictures here are result of bad fixing of my prints. They are Ilford resin coated paper not known for being all that archival. My b+w negatives of these Intruder people are pristine. I like the look of the deterioration.

Stephen Coonts

And would you believe it, Captain John Schork is now an author of aviation novels!

Captain John Shork

Not related but still within the subject Sukhoi