|

| Noire et blanche 1926, Man Ray |

Homage to Andre Breton

It would look like an abandoned pair of shoes on the waterfront,

like somebody else’s puddle on the sidewalk,

like the view from a small bridge across a small creek

forded by baptismal acolytes like sleepwalkers.

Among them, like a tourist, a would-be Jesus,

shaking his long locks, dozy Dionysius,

large head of hair on a massive head.

It would be like a moment of waking in which the trees outside

are momentarily confused in consciousness

with the design on the curtains inside the room.

It would be forbidden in this new society

to make the distinction between sleeping and waking.

The Registry of Dreams and Nightmares

would have priority over every other ministry,

open only at night, attended by

the half-awake, the half-blind, the half-deaf.

New rules issued every morning

countermanded at night.

The trains would depart today, arriving yesterday.

Obviously nothing would ever be on time. In fact,

it would be against the law to be on time.

Later rewarded. Earlier punished.

Advertisements begin with the words

“Be sure to stay away from all of this.”

The food arrives at the table long before the diners,

cleared off the tables before anyone can touch it,

surrounded with whispers of poison.

Each day’s work begins with the analysis

of the previous night’s dreams.

From Homages to French Poets, by Jamie Reid, Pooka Press, Jan 2010

|

| Noire et blanche, 1926 Man Ray |

We Argentines have a word, pajuerano, which would translate to greenhorn but not quite. Originally it was about country bred folk who did not understand the complexities of city living. In a more modern usage the word is used to describe those who are ignorant of culture and manners.

|

| Blanco y Negro, Alex W-H 2010 |

My father, with the clean flick of his wrist would hit me, on the top of my head with the flat of his knife whenever I ate food, especially chicken with my hands or broke some other awful rule of table manners. To this day when I eat chicken (and this is often Nando’s extra hot chicken wings) my nose will itch.

With age I have become less conscious of my father’s aforementioned rules of manners and I am more likely to say something I should not to my wife’s embarrassment. But when I have to impress my table manners and my demeanor can be impeccable.

Not being a pajuerano has all to do with having a good balance of knowledge of history, geography, literature and the arts. I must admit that when it is about the arts I am still a pajuerano, but I am trying to correct the fault.

Last Thursday I took Rebecca to see Man Ray, African Art and the Modernist Lens at the Anthropology Museum at UBC which is a superb, must see show that runs until January 23. I explained that in this day and age, when most of our reality is perceived as a photon-thick surface on a computer monitor or a TV screen, it can be a delightful experience to see stuff that occupies space. In the case of the show at the UBC Museum of Anthropology these are actual prints by the Philadelphia born (1890) photographer Emmanuel Radnitzky who is better known as Man Ray (interestingly in my photography book collection he is alphabetized sometimes under M and sometimes under R!) and artifacts, mostly African masks and idols of the type that Man Ray used in some of his photographs and paintings.

|

| Noire et blanche, 1926 Man Ray |

The show is a real coup for Vancouver and it shows that the Vancouver Art Gallery is not the only game in town for this sort of thing. Some might think that the fact that Man Ray used African artifacts in his photographs as an excuse for showing his photographs in what is perceived (at least by me) as a palace of anthropological political correctness. If the connection (photographs of beautiful women and African masks) might be seen by some as tenuous, who cares? The MOA show is a splendid show that all should see and for many reasons. MOA has this short explanation on the show:

The exhibit will bring to light photographs of African objects by American artist Man Ray (1890-1976) produced over a period of almost twenty years. In addition to providing fresh insight into Man Ray’s photographic practice, the exhibition raises questions concerning the representation, reception, and perception of African art as mediated by the camera lens.

|

| Blanco y negro, Alex W-H 2010 |

But first to that little rant about “anthropological political correctness”. When Rebecca and I arrived at the entrance of the museum I was shocked not to find the original large carved statues and the splendid carved doors that have always been there. They have been replaced by clear plate-glass and on the up-until-now plain Arthur Ericksonian concrete floor there are now polished (and ever shiny) tiles with a Native Canadian motif that left me cold.

I enquired about the doors at the ticket desk (overall the staff at MOA is helpful, cheerful and polite). I was explained that the museum lies on Musqueam Nation land and that the doors represented another separate, distinct and particular branch of of Native Canadians who were not of the immediate proximity. This means that the doors were perceived as an insult and lack of respect for the Musqueam Nation. On the excellent MOA web page there is this explanation:

At the top of the stairs outside the Museum is an Ancestor Figure carved by Musqueam artist Susan Point in 1997. The figure holds a fisher (an animal believed to have healing powers).

The magnificent carved doors framing the entrance to the Museum Shop were made in 1976 by four master Gitxsan artists: Walter Harris, Earl Muldoe, Vernon Stephens, and Art Sterritt. Represented on the doors is a narrative of the first people of the Skeena River region in B.C. Until 2007, these doors were mounted at the entrance to the Museum. They now frame the entrance to the Museum Shop.

|

| Kiki, 2010 Alex W-H |

At one time there was a sign inside the museum that triumphantly proclaimed the site of the museum and lands around it as Musqueam Nation hereditary property and that at some future date would be reclaimed. That sign is no longer in evidence but still in evidence is this hocus-pocus-tread-carefully-with-guilt-ridden-respect treatment that non Native Canadian Canadians treat Native Canadians. It is about an America (or whatever you want to call the land before Columbus and others came to interlope) that was free of crime, murder, rape, assassination, war, etc. The land was a paradise that would be irrevocably destroyed by the bringers of the pox, both the “small” one and the more virulent sexual one.

It was a couple of years ago that I had to photograph a Native Canadian affairs activist at the museum. The activist, a woman, pointed out that I could only photograph her by a lovely arch structure on the side of the museum that was 100% of Musqueam Nation provenance. Anything else she said would have been an affront and deemed an insult. If the museum where to go on the path of absolute-political-correctness-in-absurdity it would have to remove the long houses and totems that are in the back of the museum.

But in defense of the Museum of Anthropology I must assert here that my both my granddaughters love the museum as they are want to run on the carpeted corridors and nobody tells them not to. This little lapse in irreverence by the part of the museum staff is appreciated! They also like to touch a large carved bear where there is no prohibition.

The Museum was also a place where I have been able to watch in wonder how my 13 year-old granddaughter Rebecca has grown in sophistication. When as a little girl (7?) she asked me about certain stuff that was visible as we circumnavigated Bill Reid’s The Raven and First Men. I told her that they were scrotums and I explained their purpose.

That sophistication seems to be in lapse (or is it my own?) when I loudly asked Rebecca, “Should we go to the Bill Reid Rotunda and have a look at the scrotums?” She angrily told snapped back, “Shush, don’t embarrass us!”

I had taught Rebecca previously of Man Ray’s relationship with that wonderful creature of the demimonde, Kiki of Montparnasse (Alice Prin). I had shown her Man Ray’s photos in my photo books and my efforts to replicate or use them as inspiration to my own photography.

|

| Marie Ernst, Max Ernst, Lee Miller, Man Ray by Man Ray |

What is alarming (and predictable?) is the extent to which biographical information has become uniform ( and perhaps incorrect or incomplete by omission) on the web. My copy of Hans-Michael Koetzle’s Photo Icons - The Story Behind the Pictures Volume I, Taschen 2002 says this of Man Ray’s first meeting in 1921 with Kiki:

Shortly after moving from New York to Paris in 1921, Ray had become acquainted with the young woman, a favourite nude model in artistic circles, whose defiant charm was precisely such as to appeal to Man Ray. In his memoirs, the photographer described at length his first meeting with Kiki de Montparnasse.

One day I was sitting in a café [Café La Rotonde]. Soon the waiter appeared to take our order. Then he turned to the table of girls, but refused to serve them: they weren’t wearing hats. A violent argument arose. Kiki screamed a few words in a patois I didn’t understand, but which must have been rather insulting and then added that a café is after all not a church, and anyway the American women all came without hats… The she climbed onto the chair, from there onto the table, and leapt with the grace of a gazelle down onto the floor. Marie [I presume it was Marie Berth Ernst the wife of Max Ernst] invited her and her friends to sit down with us; I called the waiter and in an empathetic tone ordered something for the girls to drink.

|

| Lee Miller, 1930 Man Ray |

I have not been able to find that information anywhere else and I will have to go and look for a hard copy of Man Ray’s memoirs. For me it just proves that the demise of the bound paper book has to be delayed a bit longer.

After seeing the show Rebecca was yawning a tad, “I suffered insomnia last night.” I noted that she had chosen not to wear makeup on that day. There was a room adjunct to the large exhibition room where I noticed the flickering of film. We entered. There was lit red light menu that told us:

Film screenings include:

- Man Ray, Le retour à la raison (The Return to Reason), 1923, 3 min

- Fernand Léger & Dudley Murphy, Ballet Mécanique, 1924, 19 min

- Francis Picabia & René Clair, Entr’acte (Between Acts), 1924, 22 min

- Marcel Duchamp, Anémic cinema, 1926, 7 min

- Man Ray, Emak-Bakia, 1927, 18 min

- Man Ray, L’étoile de mer (The Starfish), 1928, 21 min

- Man Ray, Les mystères du château de Dé (Mysteries of the Chateau de Dé), 1929, 27 min

|

| A scene from Jean Cocteau's film Le Sang d’un poète |

I pressed the red buttons to Man Ray’s short films which with the exception of L’etoile de mer (which featured mostly Kiki’s) proved to be 3 minute films that seemed an hour long. Finally I pressed (not in the above list which I downloaded from MOA’s web pae) Le Sang d’un poète (1930, 50 minutes) by Jean Cocteau and we hit paydirt. The film was interesting (even though many people walked in and after a couple of minutes would walk out) because it featured Lee Miller. The picture here is, I think, a nice iPhone capture. Rebecca said, "You are prohibited from taking pictures." I told her, "I am pleading ignorance and nobody will mind."

It was for American high fashion model, turned-photographic-assistant to Man Ray, Lee Miller that Man Ray finally dumped Kiki (after informing Kiki it seems she threw plates at him).

It was about 10 years ago that our very own Presentation Gallery in North Vancouver had a nice show of Lee Miller’s photographs. She became, under Man Ray’s tutelage a good photographer in her own right. Some experts even suspect that many of Man Ray’s photographs should be attributed to her. In WWII she photographed the Normandy landings, the liberation of Paris and took some of the earliest photographs that revealed to the world (in conjunction to Margaret Burke-White) the horrors of Dachau.

|

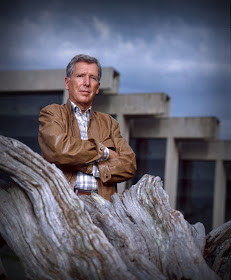

| ArthurErickson, Alex W-H |

My friend, poet Jamie Reid (whose pean to André Breton begins this lengthy blog) told me that Lee Miller had even the temerity of taking a bath (she was dirty of days of recording the destruction of Berlin) in Hitler’s bunker bathtub.

I wanted Rebecca to finally see who Lee Miller was so that she can do what many women are doing now and that is to discover another proto feminist symbol (beyond the not-so-prot0-feminist Frida Kahlo) such as photographers Tina Modotti, Margaret Burke-White and Lee Miller.

Rebecca is much enamoured to good looks these days. If the fact that Lee Miller’s elegant good looks will help her to be exposed to women with substance, that is all the better.

I snapped some iPhone pictures of Rebecca outside the museum by the relatively new little pond behind. I photographed her exactly in the location where I had photographed Erickson in the early 80s. I remember him telling me what should be behind him and how he welcomed my shot which hid (the large drift wood/stump) what was not there. Arthur Erickson had been thwarted from the very beginning (1971 when he designed the building and when it was built in 1976) by environmental concerns that a lake would help erode the nearby cliffs facing the waters of the Straight of Georgia. It was only after some persuasion by an ever so persuading Cheryl Cooper that the foot-into-the-door of the lake happened on Junne 14th 2004 when a temporary pond was installed to celebrate Arthur Erickson’s 80th birthday. The pool became a permanent fixture September 19th 2010 with Cooper obtaining financial backing from philanthropist Yosef Wosk or as I gleaned from Wikipedia:

In September 2010, a reflecting pool was added to the front of the Museum, funded by Yosef Wosk, OBC. Arthur Erickson and landscape architect Cornelia Oberlander originally intended the pool to be opened as part of the new Museum of Anthropology in 1976; now, nearly thirty-five years later, their original vision for MOA has been fulfilled. Pools had been installed temporarily only three times in MOA’s history: for a movie shoot in 1993 (“Intersection”), for the APEC leaders’ summit in 1997, and to celebrate Arthur Erickson’s 80th birthday in June 2004.

I told Rebecca, who has to write an essay for school on the significance of Lady Gaga’s raw meat dress that the surrealists of the 20s were simply ahead of her in a penchant to shock and change established order. I told Rebecca about Marcel Duchamp’s 1917 Fountain which in reality was a urinal displayed upside down. I did not tell Rebecca that Vancouver has an equivalent in Cesar Pelli’s Eaton’s/Sears downtown building which to me reminds me of a large pisser.

|

| Duchamp's Fountain |

I began this with a mention of the word pajuerano. I have been one for most of my life and it only of late, as I try to educate my granddaughters to the wonders of arts and culture, that I have begun my own personal journey into becoming a tad more knowledgeable on stuff that may not have immediate practical use but makes life worth living. I thank Rebecca and Lauren for that opportunity.

|

| Duchamp's Fountain, Alex W-H 2009 |