A moral tale of endurance in Depression-era Manitoba

by Ben Metcalfe

This story is about a fan dancer, a bush pilot, a Mountie, my father, my brother, George Lloyd, Jimmy McGuire, Fats Hamilton, the Uptown Theatre in Winnipeg, Charlie Chaplin and myself.

That is about everyone. Unless you want me to count the dog team. They were certainly in it and part of it, although I can’t speak for them, and I don’t know anyone who can at this late moment in time.

But it all began with the fan dancer. That’s for sure.

Now, there have been four professional dancers in my life of any account qua dancer. One, of course was my beautiful Aunt Vera Dudley of the Ziegfield Follies; another was Carioca, a belly dancer who performed a the Dugout, an esoteric bar in the basement of the Metropole Hotel in Cairo during the Second World War until the British arrested her as a spy; another was Margot Fonteyn, with whom I appeared as a super in The Sadlers Wells production of The Snow Queen at the Orpheum in 1957, thanks to Hugh Pickett; but before them all came the fan dancer.

Her name was Fey Baker, and she was the first, and if the trend continues, the last fan dancer in my life.

Fey was not, of course, the only fan dancer in the world at the time. It was, after all, The Depression, which had not even been capitalized as yet, or accorded the definite article, and was known simply as “a depression.” Fan dancing was a very big then, like miniature golf courses, flag pole sitting and roller skating across the continent in the summer time. Sally Rand was at her peak, and very soon to be immortalized at the Chicago World’s Fair where she would give new hope to every working girl who was not working. There were, consequently, lots of fan dancers.

Fey Baker, I suspect, was one of those girls who had been unable to get a job at Woolworth’s or dealing off the arm in a greasy spoon, although the only evidence I have for her neophytism is the fact that she traveled with her mother as her chaperone. It just did not seem reasonable to my 13-year-old mind that a real fan dancer would travel with her mother, let alone have a chaperone. I could have been wrong.

Chaperoned or not, though, she created a sensation in the clerkishly respectable little inner suburb of River Heights when she turned up as the star turn during the intermission between the double bill at the garishly new Uptown Theater.

It was somehow aptly innovative of The Uptown, that while the cheaper movie houses in the shabbier corners of Winnipeg were giving away china to get you in. The Uptown should give you a fan dancer, so to speak.

True, you did get to keep the china, but you had to see at least 48 movies to acquire a full set, whereas you could take in a full set of Fey Baker at one sitting.

Naturally, my friends, George Lloyd, Jimmy McGuire and Fats Hamilton, and my brother Robert and I, all devout if sudden aficionados of the dance, were anxious to see Miss Baker.

Naturally is putting it mildly. Considering that we were all suffering the angst of early puberty, a condition well known pathologically for its virility, virulence and voraciousness, not to mention its lack of discrimination and discretion, we were, let us face it, openly crazed with lust.

The only naked woman any of us had seen in our lives were our respective mothers, and that when we were only three at most. The chance of seeing a strange woman, especially a woman of Miss Baker’s proportions when (by all public accounts) she was stark naked, albeit tactically obscures here and there now and again by one or another of her fans, drove us into a frenzy of collective fantasies of such recherché and rococo variety as only a Seventeenth Century Florentine jade could invent ad libitum.

We were determined to see Fey Baker if she were the last thing we would see on earth. We were already going rapidly blind with desire. There was, of course, a problem. One was permitted to attend the movies only for the Saturday matinee’s wholesome fare of Tom Mix, Ken Maynard, Andy Clyde and Johnny Weismuller, whereas Fey Baker appeared only in the evening séances.

The price had something to do with it in that time - a dime vis-a-vis a quarter – but the main consideration, especially in my father’s view, was that the movies were bad enough morally in the daytime without compounding our turpitude by going to them after dark, with all the night-time’s concomitant evils.

My mother lived for the movies, but my father preferred church, which was a combination of opposites out of which they concocted the perfect compromise: my mother went to church with him on Sundays, and my father went to the movies with her on Wednesdays. I suppose it was a measure of their respective devotion that, while my mother never showed a sign of repentance or conversion in all her life, my father did succumb, over the years to the charms of Charlie Chaplin.

Indeed, even by this time, Charlie Chaplin had become for my father the epitome of all secular virtue. What with the depression on earth and war in the wind, not every prospect pleased my father, but God was still in his heaven, and only man was vile, with the exception of Charlie Chaplin.

Imagine our delight, then, to learn that Charlie Chaplin’s new film, City Lights, was going to be shown at The Uptown during the week when Fey Baker would do her own stark naked thing with the fans!

Instantly, with the perception of young hawks, we discerned the slightest, hair-wide fissure in my father’s most fundamental principle, and forthwith we began a campaign to breach it wide enough to let two pubescent voluptuaries pass through. Our wedge into his resolve was the thought, perfectly plausible at the time, that unless we saw Charlie Chaplin’s new film now, at night, we would never see it in our entire lifetime.

From this distance in time, and in the taunting light of my own failures later to see through the blandishments and deceptions of my own children, I do not mean to gloat when I say that my father swallowed our rationale hook, line and sinker. I beg his forgiveness now, but we were uncommonly proud of our guile at the time. The prospect of his sons never seeing Charlie Chaplin’s film was too much for him to bear, and he cracked.

And as soon as he cracked, George Lloyd, Jimmy McGuire and Fats Hamilton had but to convey the news to their own Dads, and they were as broken reeds before a withering blast of boyish pleas for justice and equity in our block.

I can still hear Fats Hamilton’s old man musing along the lines that, if Joseph Bennet Betcalfe would make an exception in this case, James Hamilton sure as hell might, too.

And so it was settled. We all went to see Charlie Chaplin and Fey Baker in City Lights on the opening Monday night: my brother and I, George Lloyd, Jimmy McGuire and Fats Hamilton.

And all our fathers.

And we all agreed it was a hell of a fine movie. My own father enjoyed it so much that he went to see it again with my mother on her regular Wednesday night out.

As for the fan dancer, her name never came up, except when the gang was in a committee of the whole the following days in the school washroom, hallways, lobbies, playgrounds, street corners, garages, tree forts, empty box cars, woodsheds, public libraries and anywhere else we could get up a quorum, which was usually any two of us, or one if necessary.

From one meeting to the next, it was moved, seconded and carried that Miss Baker had revealed more and more and more of her most intimate body to our committee than she had shown advertently or inadvertently to anyone.

Within a matter of days, in fact, it became clear to us all that she might as well have left her mother the chaperone at home, for all the good she did, and her fans to boot, for all they concealed of her flesh. Very soon, then, we realized that she had singled us out in the front row, where we had persuaded our fathers that we could see City Lights better, and had been making desperately lewd attempts to get us to go home with her after the show.

If one of us forgot momentarily some particular suggestive gesture on her part, or some interesting detail of her body, like a hair or an unusual coloration of the flesh in some out-of-the-way crevice, another would remind him of it without the slightest disjunction of continuity either in theory or in practice.’

The Uptown held her over for two weeks, but although she left town, we held her over as long as we could in our committee meetings until something better turned up, which it did not.

And then the big story broke…

The first I knew of it was from my father mumbling, “Well what do you know about that? “ and shaking his head reflectively as he passed The Winnipeg Tribune to my mother over their after-supper cup of tea.

“Hmmmmmppphhh,” said my mother, after reading the headline and passing the paper back to my father. My mother never read more than the headlines, and then only at my father’s suggestion. Usually, he would read the entire edition, from the front page disasters to the back page horoscopes, then fold it up and put it down with the comment that there was nothing in the paper again. My mother knew that he was keeping an eye out for the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse and would let her know in plenty of time it they should turn up at Portage & main. Meanwhile, she relaxed, or worried about whether Clark Gable was suited to Carol Lombard.

This unusually sanguine attitude of my father to a piece of news did, however, arouse my own curiosity, and I turned my attention from my homework to the front page where the main headline screamed out in black letters the size of boxcars:

FAN DANCER & BUSH PILOT

DOWN IN NORTHERN BLIZZARD

Yes, it was none other than our own Fey Baker, who had gone north from her Winnipeg engagements to entertain the miners in the then-new frontier mining town of Flin Flon.

On the flight back, the plane had disappeared, and was long overdue.

Now, whereas the Fey Baker fantasy had been held over, as I say, by our committee as long as it was feasible, it had been receding and becoming vaguely blurred and generalized quite naturally before the onslaught of the Stanley Cup play-offs and the careers of the brothers Conacher, etcetera.

The news of Miss Baker’s plight jolted us back to fantasy.

Without much delay, our committee met the next day in every possible nook and cranny of school and neighborhood to review this revitalizing turn of events, to concoct and embellish new scenarios and to take turns to play the role of bush pilot, whose luck we could not entirely believe.

The fact that the fan dancer and her escort were lost in a mean temperature of some fifty below zero did not chill our imagination. Indeed, our imagination was too preoccupied even to think if about providing Miss Baker with anything warmer than her fans. How she endured, I have no idea.

A fan dancer lost in the wilderness with a bush pilot! How can you impossibly improve on a story like that?

Well you cold send a Mountie out to look for them with a team of sleigh dogs, couldn’t you?

You certainly could, and they certainly did, and the ensuing tension was even more exquisitely unbearable.

Hitler was taking over Germany from Field Marshall Hindenburg. Mussolini was preparing to seize the entire Mediterranean Sea, Britain was going off the gold standard, Dillinger was shooting up the United States, Roosevelt was launching his New Deal, the Liberal Party of Canada had been given a well-earned rest from power by the conservative Janitorial Party, and Japan was moving into China.

But not as far as our committee was concerned. For us there was only one current event: Topic A.

Unaccustomed as we were to reading more than the funnies and the hockey scores, we were now unconscionably interested in the front pages of the daily press insofar as they informed us the progress of the search for the fan dancer and her bush pilot and, as was bound to happen, the Mountie, too. Because, soon, enough, all three were lost, and apart from everything else, this created complications in our committee.

We did not quite know, in our mid-western simplicity, how you handle this kind of ménage à trois. If we had even heard of a ménage à trois.

The best we could come up with was that the bush pilot and the Mountie would simply have to take turns being in love with the fan dancer, while the fan dancer would simply have to be in love with whomever stayed in the cabin (we eventually built them a cabin, but Miss Baker still naked) while the other one went out to hunt for food and chop firewood.

There was a certain reluctance for a long time, too, for many of us to become the Mountie. Not that we had anything against Mounties at the time. It was just that we had all got so comfortable in the role of the bush pilot.

Meanwhile, the search went on. And, eventually, of course, the most publically exposed ménage à trois in Canadian history was found and brought back to civilization, where, as they returned, there was a great deal of public speculation as to whether Fey Baker would marry the bush pilot or the Mountie,

It was written into the manners and the mores of that place and time that no girl, fan dancer or not, could spend so long in the bush with two men without marrying one of them very soon.

My mother, who was a follower of such things as Rose Marie in real life, figured it would be the Mountie who got the girl. But my father pointed out that it would have to be the bush pilot, because the Mountie was under marrying age according to the prevailing stringencies of the Force. And there the matter ended as far as my parents were concerned

As for our committee, we continued to raise the matter for speculation some time after it had dropped by society as a whole.

We dallied, briefly, over the rumor that the sleigh dogs had suffered badly in the event, having been eaten by the Mountie the bush pilot and maybe even the fan dancer, too, just to keep up their strength in the rigors of the Manitoba winter. But this was never established incontrovertibly, though it has a plausible enough ring to it.

Life eventually resumed its everyday course. George Lloyd became and anti-submarine bomber pilot in the RCAF, and survived to retire and play golf; Jimmy McGuire was shot down and killed over the North Sea as an air gunner with the RCAF; Fats Hamilton has been trying to console his parents for the loss of his brother Jim, with the Seaforth Highlanders; all our Dads are gone, of course. The Uptown Theater is now a bowling alley; and you know what happened to Charlie Chaplin, apropos which I must confess to the shades of those Dads that we did, in the event, get a number of other chances to see City Lights, although we had no way of predicting Television then. And, anyway, I have since figured that we are quits, seeing as how we helped them get to see the fan dancer, too.

Maybe the bush pilot and the Mountie are still around and will come forward to sue me, and they are most welcome. There’s a couple of things I would like to ask them.

As for the fan dancer, I never heard of her again, but I can say fondly and sincerely now, as Jimmy Durante might have said, “Good night, Miss Baker, wherever you are.”

And with Browning, “How did we love you? Let me count the ways. “

First published in the January 1980 Vancouver Magazine

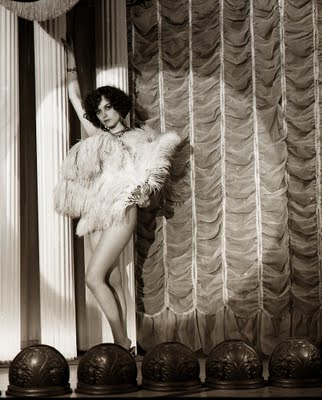

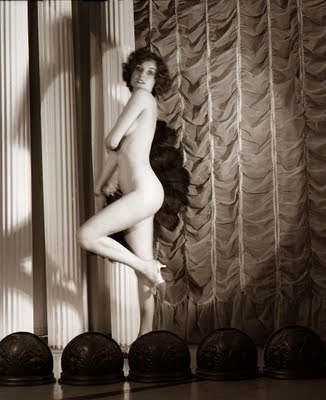

Behind Lady Fey

The photograph that appeared in the January 1980 issue of Vancouver Magazine which was used to illustrate one of my favourite pieces ever written by anybody (in this case by my friend, E. Bennet Metcalfe) has an interesting story on how it came about.

In the late 70s and early 80s Vancouver Magazine was a Mecca for the best editorial illustrators of the city and the country. These were Marv Newland, Brent Boates, Ian McLeod, Ian Bateson, Barb Wood, Bernie Lyon and more that I cannot remember.

In my presence (probably an editorial gaffe as I should not have been privy to the conversation) art director Rick Staehling proposed Metcalfe’s piece should be illustrated while the editor, Malcolm Parry argued for a photograph. Lucky for me Parry prevailed and I was assigned to shoot it.

I chose a gay review club on West Pender Street called BJ’s because they had an old fashioned type stage and a spotlight. As my subject I chose my blood sucking friend Inga V who was an experienced dancer with and sans fans. Plus she had the added talent of being a makeup artist and stylist. I don't remember where we obtained the feathers. They probably had them in the costume department of BJ's.

I have always been proud of my ability to shoot well-exposed and sharp photographs. For the first time (and last) I saw myself focusing and then unfocusing my lens a tad, to get and old-photograph blurred look. I helped this along by using a slow shutter which might have been 1/15 second or slower.