Everyone knows that Edward Lear was queer for runcible things, like hats and spoons and cats, but does anyone know what runcible is? I doubt it very much.

The only possible exception could be myself. At least I have tried to find out, not alone for the sake of disinterested scholarship, although scholars are welcome to the pickings, but because I have a runcible cat.

Since Lear implanted it there in the late Nineteenth Century, the word runcible has been entrenched in facetious English usage; if rarely called upon, always available. Yet no one, not even the fastidious H.W. Fowler, nor his successor Sir Ernest Gowens, nor the great Oxford Dictionary itself, has dared to explore it, define it, or at least venture, if ever so roughly, when and how it could be used.

Except that it became suddenly my own ineluctable portion to enquire into its mysteries root and branch, I, too, might have continued mutely to acquiesce in its existence without knowledge of its meaning.

Which, thinking on it, is not precisely true, for it is the very pith of runcible that one knows its meaning without necessarily knowing that one knows it – something, in other words, that can be learned, not taught. Else how, for instance, should I have perceived without instruction that I have a runcible cat? Yet I did.

It was perhaps his contrast with the other one, who is definitely an unruncible cat, if that is the proper word for a cat that is not runcible, although I shall be coming to that problem shortly.

Certainly, everything else being equal, if you happened upon a runcible and an unruncible cat in the same moment, you would know immediately which was which. I know that I would, although I would not go so far as to say the same for hats and spoons.

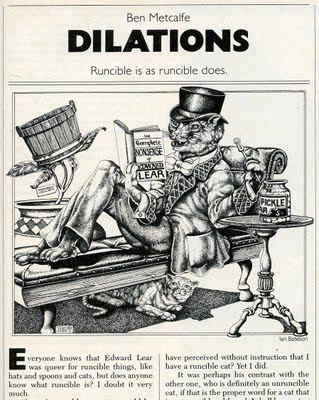

Our runcible cat’s name is Mr. Smith. At any rate, that is what we call him. If T.S. Eliot was right about cats, and I daresay he was, Mr. Smith has two other names: his real name and the name he calls himself. Mr. Smith, however, is the only name I can vouch for; and he does answer to it in his way.

Our unruncible cat’s name is Hui Neng, after the Sixth Patriarch of he Ch’an Sect (638-713), the famous Dhyana Master of the Tang Dynasty, which has nothing whatsoever to do with his unruncibility but only with the fact that I was given him by an equally unruncible shopkeeper in Chinatown. He, too – I mean Hui Neng – probably has two other names, both secret, and once had a fourth, Candy, given him by his previous proprietor but rejected by myself as utterly inappropriate.

Now, in this short space, I have already extended the word runcible into two derivative forms; i.e. unruncible and unruncibiliy, both admittedly too loose for comfort, so it is imperative that we look into Lear’s original word lest we wallow in misconstruction.

The word runcible itself is apparently an adjective of sorts, though with subtly plausible affinities to an unused (because unknown?) verb, which may or not be runce, or even runc, and, whatever it is, may or may not be transitive; it is of no consequence.

It may be best at this point, too, that I remark that I am merely a writer, neither a grammarian, nor an etymologist, nor a linguist, but merely a writer.

Be that as it may, the deepest one can dig with satisfaction into the roots of the word runcible in the Oxford, or any other dictionary of the English language is runci.

Before runci, one gets runca, as in runcation, meaning the act of weeding; and words like runch (a kind of weed); runchie (another word for weeds, used generally by rurigeneous, that is country folk); and after runci, runcle ( a kind of beet). All of which take us nowhere, and leaves cats, if not hats and spoons, far behind.

So back to runci…

The first possibility is runcinate, an adjective signifying a surface that is saw-toothed, with lobes curving towards its base, deriving from the Latin runcina, meaning plane, but apparently often mistaken for a saw.

This characteristic might well occur in spoons, I suppose and (although God know how) also in hats. But while it is more or less true that a cat’s tongue is more or less runcinate, it does not seem quite enough to justify calling the whole cat runcinate, let alone runcible. For would not that make all cats runcible? And is it not the whole point that all cats are not runcible?

Hui Neng would certainly testify to that. And I imagine that Lear would agree. So much for runcinate.

The second, and last, possibility is runcival, meaning several and mutually unrelated things, but interesting at first sound because, if one were to imagine a Spaniard enunciating runcival, one would certainly hear him say runcible, for Spanish-speaking peoples, especially Castillians [sic], cannot, or at any rate do no, sav V, but turn it into B, as in Biba Zapata!

Would that Edward Lear had been even remotely Spanish, and at least half our quest would be done. He was, of course, not.

Neither is it recorded anywhere that he was afflicted by one of those charming impediments not unusual in the speech of the English educated classes, the most common of which turned the R into a W, as in Wichard, or Wonald, or Wuth. Or wuncible? But, of course, that wouldn’t do; and in any case he was, again, not.

Perhaps, where there is plenty of room for speculation, runcival, or rouncival as it was commonly spelled after its first appearance in the Sixteenth Century, wormed its way into Lear’s yeasty mind, fermented there and gave off a more esoteric form.

It is a curious enough word in its own right, thought to derive from the place name, Roncevalles (bramble valley), a tiny, lovely place in the Pyrenees not far from Pamplona. And, while today it means only a large variety of garden pea, it was once used to denote giganticism, robustiousness, a heavy fall or crash, a form of alliterative verse, a witch, and was perhaps the best of all possible nouns for a woman of large build and boisterous or loose manners. Curious indeed, and precisely the word for Judy LaMarsh, but not for our Mr. Smith. And least of all for Hui Neng.

Yet Mr. Smith is undeniably runcible in the precise way that Edward Lear unquestionably meant the word to signify, whether or not it seethed up out of his awareness of runcival.

How so, if he is not pea-like, alliterative or witchy, and not even rarely falls heavily about the place like a big, boisterous woman (although he is big); how so is Mr. Smith or any cat runcible?

It is not because of the word, of that much we can be sure.

Cats do not fit themselves to ready-made words, not runcible cats, that is. As the line comes before the meaning in calligraphy, so does the runcible cat appear before the word.

People and most others – Hui Neng, for example make themselves look like available words; such as beautiful, slim, clever, rich, adorable and popular. Not so a runcible cat.

For a runcible cat there is no word, wherefore he is runcible. It is as simple as that. Or as the scholars say, Q.E.D.

Edward Lear, however, knowing that people need words whether or not they understand their meaning, and being the greatest wordsmith of us all, smithied us a word that clearly means everything and nothing at once.

And he employed it with such aptness as left nothing to doubt. As in…

His body is perfectly spherical,

He weareth a runcible hat.

Or…

They dined on mince and slices of

Quince,

Which they ate with a runcible spoon…

Or…

He has gone to fish, for his aunt

Jobiska’s

Runcible Cat with crimson whiskers!

Runcible is as runcible does, of course, notwithstanding the fact that no one knows what it does, and that probably goes for hats and spoons as much as it does for cats, although I do not claim to speak for hats and spoons in this case. Only cats.