The Grand Coulee Dam is a hydroelectric gravity dam on the Columbia River in the U.S. state of Washington. In the United States, it is the largest electric power producing facility and the largest concrete structure. It is the seventh largest producer of hydroelectricity in the world, as of the year 2008.

The Grand Coulee Dam is almost a mile long at 5223 feet (1586 m). The spillway is 1,650 feet (503 m) wide. At 550 feet (168 m), it is taller than the Great Pyramid of Giza; all the pyramids at Giza could fit within its base. Its hydraulic height of 380feet (115 m) is more than twice that of Niagara Falls. There is enough concrete to build a four-foot wide, four-inch deep sidewalk twice around the equator. It was inaugurated in 1942.

Wikipedia

In June 2002 I went to a convention of the American Hosta Society which was held in Spokane. On my way back to Vancouver I made a detour to visit the Grand Coulee dam. The American paranoia of 9/11 had yet to materialize in its extremity and I was given free rein to take pictures anywhere I wanted and nobody questioned my considerable photographic equipment. I would suspect that photography now would be by strict permission.

When I heard the roar of the cascading water and saw the huge concrete structure I felt the marvel of human engineering. It was a marvel from my past when concrete was good. In fact in the late 50s both Bing Crosby and Bob Hope advertised the goodness of concrete highways (the interstate highway system that was begun by President Dwight D. Eisenhower). Wonderful cable suspension bridges had yet to collapse and show the over confidence of that human engineering that had a spell on all of us before cracks began to literally appear on concrete structures.

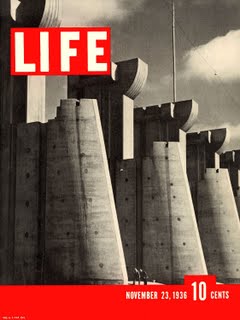

A young boy, 13, in November 1936 noticed and marveled at the first cover of a large new magazine called Life. On that cover was a monumental image of Fort Peck Dam on the Missouri River in Montana. The photograph was taken by Margaret Bourke-White who was to achieve other firsts which I have noted here here and here. In my classes at Focal Point and Van Arts I often tell my students on how kind photography has been to women like Julia Margaret Cameron and Margaret Bourke-White. Other women photographers like Lee Miller and Tina Modotti are now finally getting their due. I have quite a few friends who are suffering Parkinson’s and I noted here that Parkinson’s ended Margaret Bourke-White’s career.

It is for those above reasons that sooner or later Abraham Rogatnick and I came to discuss Margaret Bourke-White’s achievements. When I opened the subject Abraham pounced on me with glee to tell me of his excitement when he had seen that Life cover at age 13. “I have never forgotten that sense of wonder that hit me when I first saw it.”

It was perhaps the same wonder that I felt when I gazed on the waters of the Grand Coulee. I was a tad frustrated as I was alone and I could not tell anybody of my feelings. In fact I felt like shouting them. Leaving the Grand Coulee all I could do was to play Pandolfi’s (a somewhat obscure 17th century composer) violin sonatas. They almost did the trick. Only human company would have fulfilled my feelings.

Talking with Abraham about architecture was like watching the great turbines (I had to imagine them since I did not see them) turn and convert the force of the water into electricity. It was electricity and the chemistry wonders of such innovative companies as Dupont, Kodak, ALCOA and 3M that would make our world a better place for all. Alas (a favourite expression of Abraham and of Shakespeare) chemical spills and nuclear waste and spills took care of our faith in technology and science. And Dupont's non stick pans caused cancer. The wonders of computer chips don’t satisfy as we paradoxically wish for smaller and smaller helpings of them as they are made ever more efficient in performance and in size.

What I miss is the solidity of objects that I can see and almost begin to understand. I may have failed electricity in college but I still have a vague idea of the difference between inductance and capacitance. I comprehend the basics of strength of materials so I know why some bridges collapse. But I cannot fathom XML, Leopard or Apache. I cannot hold them in my hand. I once adjusted the gaps of my VW Beetle spark plugs and tuned the engine using my ears as the standard. All I can do with Rosemary’s Audi is put in gas and windshield washer fluid. The over-complexification of things has left me confused, unsatisfied and melancholy. I long for beautiful buildings, powerful dams and Lockheed Constellations. I get some small comfort when I hold my 1953 Leica IIIF. It is solid, beautiful and almost understandable.

I miss the Ned Pratts, Ron Thoms, Arthur Ericksons and Abraham Rogatnicks of my life. These were solid men much like the structures they designed and built. They spoke of things that made sense. They made us feel that the future, our future, was one of urbanity in all senses of the meaning of that word.

more Grand Coulee and Bob Bose